I don’t remember learning about AIDS. When I started high school in 2005, it was frequently used as a homophobic insult or punch line – Gays give you AIDS – so I spent my teenage years denying any sense of difference for risk of being connected with it. Forced into submission by a post-Section 28 landscape, I didn’t want to be seen as one of “them”, as an “other”.

This, something I’ve seen many queer people my age do, leads to a lot of denial and judgement. I still remember claiming I wasn’t interested in feminine boys because “I’m gay so I like men,” when really, it was about separating myself from visible queerness, propping up a structure that idealises masculinity, and internalising homophobia in the process. However, now, in my late twenties, I strive to be visibly queer and not to frame my desire or existence through a hetero lens. This came from an understanding of queer history and a grip on what it all meant politically.

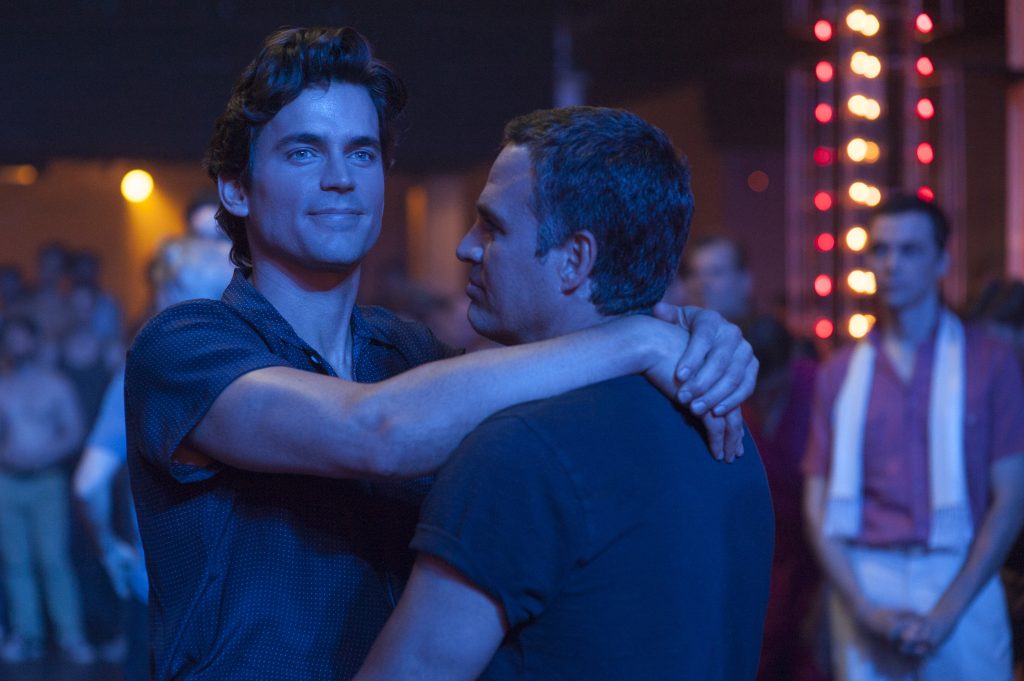

In my early twenties, I began to uncover the history of AIDS within the queer community. The Normal Heart, Larry Kramer’s seminal play, was adapted into a film in 2014 (my second year at university) which created an entryway through which Angels in America, Parting Glances, Buddies, Longtime Companion, and 120 Beats Per Minute walked. The latter introduced me to the global political group ACT UP, something I’d heard referenced on the Original Broadway Cast Recording of Rent (yes, I’m that kind of gay) but had never delved into. Documentaries followed this; How to Survive a Plague, We Were Here, and United in Anger, to name a few.

Which brings us to It’s A Sin, Russell T. Davies’ latest drama currently airing on Channel 4 and available to stream, in full, on All4. The show follows a group of friends, mostly gay men, in 1980s London as they shed the skins of their small towns and dive head-first into the hedonism of queer life as it was at the time. Of course, slowly, a disease starts to emerge – referred to as a “gay cancer” – caught through having sex. Some of the characters reject this, seeing it as too perfect an illness when sex is what most homophobes linger on, but nonetheless, the reality becomes ever more apparent.

Overall, my Twitter feed has been divided on the show. A lot have heaped praise onto it, calling it a “masterpiece”, “important”, and “vital”. People spoke of watching it with their husbands, or they reassured teens (watching, in the dark, with the volume down) that it would “get better” (though, whether this was necessary is up for debate). I saw friends talk about how educational the show was, how it filled the cavernous gaps school left, and they were beginning to understand how bad it had been. Others, admittedly a smaller group, voiced valid criticisms; where are the queer womxn? Trans people? Sex workers? Those who were crucial in the political fight against government ignorance and were also infected by the virus? For four years, as Sarah Schulman notes in her book The Gentrification of the Mind, AIDS was not considered a disease that affected womxn. As such, they couldn’t gain access to treatment, which at the time took the shape of experimental trials, because they were considered “unreliable” by pharmaceutical executives. People have also asked what about intravenous drug users, gay and straight, who were significantly affected by sharing needles? Are these stories not worthy of dramatization too?

It made me wonder about how queer history is told on screen, or, indeed, history at all. If I wanted to learn about other historical events, like the World Wars or 9/11, there is a lot that can be found. But the AIDS epidemic is so rarely dramatized that there are significantly fewer places to look. Of course, each time any new show or film comes out, there are inevitably those who like it and those who don’t. But LGBTQ+ content, which still feels few and far between, falls under a specific microscope. Whether that’s due to conversations about queerbaiting, sanitisation of experience, or too much consideration being given to a straight viewer, they have felt lacking and, almost always, overwhelmingly white, cis-gendered, and male-oriented. Yet because queer life and, more specifically, the widespread impact of the AIDS epidemic on various cultures and communities, is so varied, there is still so much left to look at.

In recent years, TV and film have made attempts to spotlight those areas left uncovered. For example, Pose examines the effect on the New York Ballroom scene, primarily frequented by black and brown, queer and trans folk, as well as sex-workers. While there has been growth, there has been significant backlash against the homogenisation of queerness too. The Prom faced backlash for James Corden’s performance, The Boys in The Band for being potentially outdated and too white, Happiest Season for being too middle-class and also too white. The question that so often arose was: who it was for? The answer: white gays and straights.

The idea that only dramas centred around cisgender (often, but not always, white) gay men and women are considered the history of queerness on film and TV leaves a lot to be desired. It simplifies the actual history. The boys of It’s a Sin, for example, are all likeable, young, attractive men, but history is more complicated than that. It feels like positioning experiences outside the white cultural experience (either gay or straight) as central is not an option. To air at primetime on a Friday night on terrestrial television you need straight people, and so it will always be watered down.

I’m not advocating for queer folk to court the mainstream – in fact, I’d rather they didn’t. But it corrupts the narrative of queer history when a particular type of queer story is the only type of queer story that most people see. That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy It’s A Sin. I did. I liked its performances, its emotion, and its representation of how people coped in the face of a crisis. It’s more that it is an example of what I’m trying to articulate. Just because it is a certain type of queer story, doesn’t mean it isn’t good or doesn’t have its merits. It just can’t be the only type of queer story.

It’s A Sin is available now.

Also Read: Is Queer Autobiographical Cinema Subtly Political?

1 Comment

Comments are closed.