The striking opening chords of Lana Del Rey’s “Born to Die” swoop in like a shockwave at the end of Xavier Dolan’s film Mommy. Though the film has been laden with bold music choices (from Oasis to Celine Dion, Dido to Ludovico Einaudi), the cinematic and ethereal violins ring in a perfect ending as troubled teen Steve escapes the clutches of two guards at the institute he’s been committed to and runs towards an unknown future. It’s a choice The Fader dubbed “a music snob’s worst nightmare”, but Xavier Dolan has become known for choices like this, for popular music taking centre stage and the wealth of genres he pulls from the very definition of eclectic. Since his debut at Cannes in 2009, his needle drops have become iconic in and of themselves.

As most filmmakers do, Dolan knows that good music can make or break a film and that a well-timed needle drop (defined as dropping “the right song at the right moment” in a movie) can clinch it. Since the beginning, music and film have been closely linked with pianists accompanying silent movies with pieces written explicitly for each. Then, of course, there are those famous movie songs; “Moon River”, “Don’t You (Forget About Me)”, or “Let It Go”, for example. These were all written with the movie in mind, to fit with its style and tone. But taking pre-existing music, with a context and lifeblood all of its own, and trying to give it new meaning within a different medium is something else entirely.

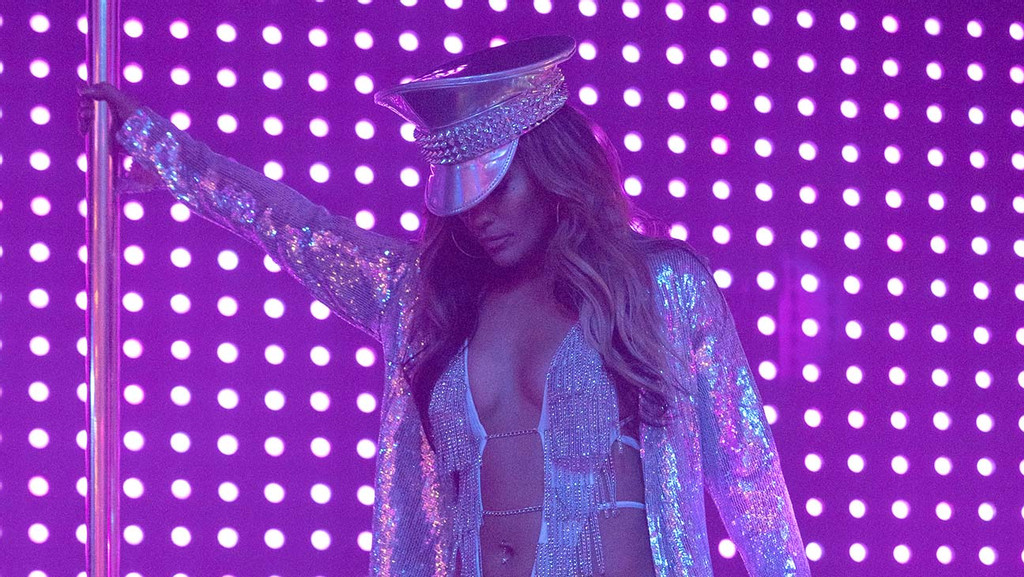

Take, for example, Lorene Scafaria’s modern masterpiece Hustlers. Its needle drops include Janet Jackson (twice), Britney Spears, Fiona Apple, and Rihanna. In a story that considers the disproportionate reactions women, namely strippers, face when committing crimes vs. the white-collar criminals on Wall Street, the music used brings into question the idea of femininity within the culture. Jackson was blacklisted after a wardrobe malfunction during the 2004 Super Bowl Halftime Show. Her male co-performer, Justin Timberlake – who, arguably, was more at fault – received 5 Grammy nominations mere weeks later. Timberlake, funnily enough, contributed to Spear’s public shaming, too, claiming her virginal image was purely constructed. But, as those who watched the recent documentary will know, Timberlake was not the only man whose fingerprints appeared on the guide ropes of Britney’s public breakdown in 2007. As for both Apple, a ‘90s feminist icon, and Rihanna, a contemporary pop star too often shamed for her powerful sexuality, their music serves as an example that, no matter how you present yourself, women don’t ever seem to please the patriarchy. Their status as symbols is one thing, and that is before you even mention the lyrics to the featured songs, all of which feed into Hustlers’ narrative that Scafaria included specific lyrics within the script itself. Jackson’s opening line to her 1986 hit sets up the movie: “This is a story about control”, which speaks to the autonomy of the women in Hustlers as they try to regain a sense of control amidst the 2008 financial crash.

Scafaria, like Dolan, may be one of the most forward-thinking when it comes to her needle drops, but many are not far behind. Take Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, a film that features no score or soundtrack until its final moments when the overwhelming sound of Vivaldi’s “Summer” blares into life at a concert. Or in Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha, Frances dances down the street with youthful jubilance to Bowie’s “Modern Love”. Or Barbra Lewis’ “Hello Stranger” crooning from a jukebox as Chiron and Kevin are reunited in Moonlight. Or Merab dancing to “Honey” by Robyn, cigarette in hand, for his lover interest Irakli in And Then We Danced. The music in these scenes is like a revelation, a link to the emotion and the feeling the director is trying to portray. Heck, a good needle drop can even make mediocre movies into something a bit better; Spring Breakers’ bizarre montage to Spears’ “Everytime”, Magic Mike XL’s strip tease by Joe Manganiello to “I Want it That Way”, or The Verve’s “Bittersweet Symphony” closing out teen drama Cruel Intentions.

Secretly, we all do it ourselves. Earphones in on our daily walk, we might play a song that makes us feel like we’re in a movie; or on a long car journey, we’ll look out over the landscape and feel the song on the radio become the soundtrack to our existence. We use music to move through the world, to comprehend it. When we hear a great song, Zadie Smith wrote, we are “in debt to its beauty” and feel an “obligation to repay that debt”. The question is, how? I think it’s in building connections, applying reverence, giving a song a special place within your emotional consciousness and letting it become a part of your narrative. To this day, I can’t listen to Joni Mitchell’s “A Case of You” or Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide” without returning to the emotions those songs stir in me, without thinking of loss and change. So music, in its mere existence, feeds into our understanding of ourselves.

It speaks volumes, then – if you’ll pardon the pun – that good music used well can elicit such a response in an audience. It drums up emotion, fondles the heart, and taps the mind to create a metatextual experience. Music brings its baggage with it, and it’s up to the filmmaker to utilise it, as Scafaria and Dolan do so well, to fit within the context of the story they’re telling. We feel the excitement within us when we hear that opening note, and then the required emotion comes flooding in.

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On BFI Flare

1 Comment

Comments are closed.