The future. That’s what everyone is talking about. After a year of online film festivals, with unprecedented access to audiences all over the UK and beyond, normality is a glimmer on the horizon. In that faint glimmer, however, there are questions; what benefits have there been as a result of this shift? What does it mean for filmmakers and artists? Will festivals revert to their previous models of exclusivity as soon as they are able to?

In the immediate, one would imagine, that might not be the case, and not just because overseas travel and social distancing will be with us for a while. Even before the pandemic, the London Film Festival, also programmed by the BFI, made efforts to extend its reach outside of the capital with a select number of more mainstream festival picks screened in cinemas around the country. In 2020 they moved beyond those safe bets to hotly anticipated films such as Chloe Zhao’s exquisite Nomadland and Francis Lee’s period romance Ammonite. Admittedly, these were not “nationwide” in the classic sense – i.e. available everywhere – but, rather, in 12 cinemas in major cities from Manchester to Edinburgh.

The idea of looking to the future, however, applies not only to the festival format but to the films themselves. For the most part, film festivals act as a springboard, as an open sea of mostly unvetted titles. Sure, quite a few of the more prominent films arrive with an element of prestige already bestowed on them by other festivals (some in this year’s Flare line-up have appeared at Outfest, TIFF, and more) but there is also a chance to uncover something new, something exciting and different. In that way, festivals can indicate what is to come by premiering fresh-faced films looking to establish themselves, and BFI Flare 2021, a festival that began in 1986 and dedicates itself to LGBTQ+ film, indicates that documentary is ramping up significantly.

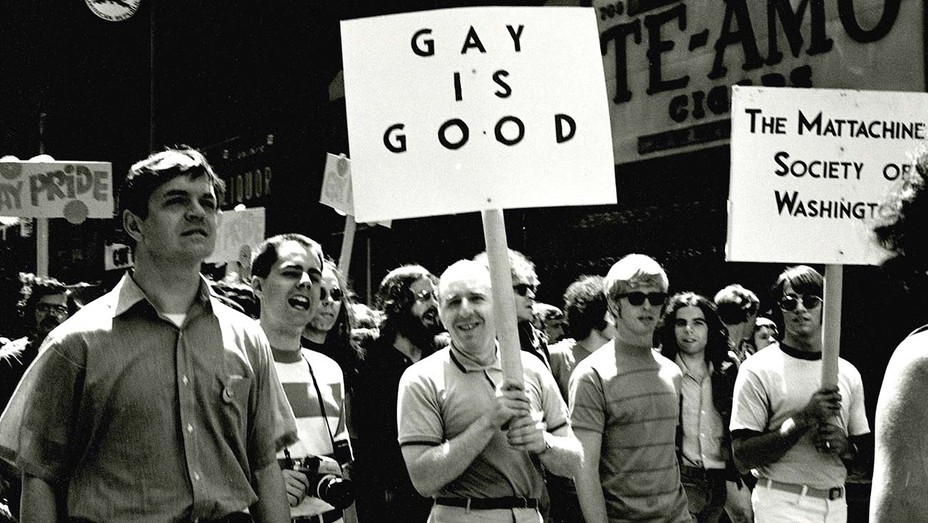

Rebel Dykes (June 2021) tells the story of lesbian activists with plenty of anti-nuclear protesting, sexual politics, and anti-Thatcher activism to boot. Directors Harri Shanahan and Sian A. Williams combine archive footage with interviews and animation to create a genuinely punk-feeling documentary that is an excellent antidote to mainstream films’ more assimilationist messaging. What’s also soothing is the trans inclusion within the radical lesbianism, which the documentary makes a point of addressing – this seems pertinent given the current state of trans rights and feminism in the UK. Elsewhere, Cured (TBC), a more typical feature, documents the campaign lead by LGBTQ+ activists to remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). It features hard-to-stomach descriptions of “therapy” thrust upon LGBTQ+ people over time, and interviews with those who fought to remove it. Meanwhile, Mama Gloria(TBC), a far smaller affair than the aforementioned two, follows Gloria Allen, a trans woman and activist in her Chicago home. Throughout the film, she meets up with those she has inspired, her old school friends, and her family to trace her life and legacy, creating a touching portrait of a too-often ignored icon.

Less impressive, it might seem, is the fiction film on display. This is not to say that most weren’t, at the very least, enjoyable in some way, but for the most part they felt like somewhat derivative versions of things that have come before. By far the most original was The Obituary of Tunde Johnson (TBC), which follows a Nigerian-American teenager who is shot by police officers during a “traffic stop”. This leads Tunde (Steven Silver) to be stuck in a time-loop in which he is forced to live the same day repeatedly, where he is always killed – in differing scenarios – by a police officer, only to wake up back in his bed. The clever weaponizing of a Groundhog Day narrative places a viewer in constant fear and awareness of the police, which works to emulate the state of mind of a young black man, like Tunde, in modern America. Unfortunately, the melodrama surrounding this premise – that Tunde is secretly dating a hot, chiselled jock who has yet to come out – is far less exciting and innovative.

Outside of this, films like Boy Meets Boy and Sublet both attempt to go for a mash-up of Richard Linklater’s Before trilogy and Andrew Haigh’s Weekend, to varying results. Sublet, the marginally better of the two, struggles to establish what it really wants to say and flounders around in predictable plotlines and stereotypes. Boy Meets Boy trades in Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy for two young gay men – one British and one German – and swaps out Vienna for Berlin as the two spend 10 hours together before one has to catch their flight back to the UK. The relative simplicity of films like this – that it’s just two people talking for two hours – is far harder to capture than it might appear, and neither can offer up much that is genuinely original. As for Firebird, the flashy and sexy period drama set in Soviet Russia, it feels more like something for a Sunday night on the BBC. It’s as if they want to capitalize on the success of recent romantic dramas like And Then We Danced or God’s Own Country (both of which screened at the festival in 2020 and 2017, respectively) but lack the authenticity to do so, instead offering something that feels lukewarm overall. It desperately wants the emotional weight of Portrait of a Lady on Fire within a military setting like Moffie, but unfortunately, all it does is remind you there are better films out there you could be watching. Speaking of other movies, both The Greenhouse and the semi-autobiographical Jump Darling try their best to bring some zazz but, for the most part, don’t quite stick the landing, even if both feature solid performances. Especially the latter, which brings us acting legend Cloris Leachman’s final performance, which is, of course, nuanced and touching.

Finally, the most egregious of all might be Cowboys, an American drama starring Steve Zahn and Jillian Bell. It tells the story of a trans child, Joe (Sasha Knight), without really considering the trans perspective. Written and directed by a cisgender woman, Anna Kerrigan, the story revolves around how two thinly drawn parents, Troy and Sally (played by Zahn and Bell, respectively), each navigate the information that their child is trans. Sally refuses to believe it isn’t more than just a phrase and refuses to buy toys that aren’t “meant” for girls, whilst Troy, a temperamental alcoholic, is more accepting but is also facing his own battles. In light of this disagreement, Troy kidnaps Joe (who is constantly put in cheap wigs), and they set off for the Canadian border on horseback. In the end, Cowboys results to nothing more than a sensationalist drama for straight and cisgender folks that shuns the perspective of the queer child who should be at its centre.

Ultimately, BFI Flare is uniquely positioned as a beacon of queer cinema in the UK and its highlighting of films like Rebel Dykes – which they previewed in 2016 – and their commitment to offering independent queer film a platform. It seems that, for all of us, 2020 has had an effect. Last year’s festival, which was one of the first to move online in mid-March as the UK went into lockdown, offered up the seminal documentary on trans representation in the media, Disclosure, as well as the aforementioned military drama Moffie. Other highlights included Isabel Sandoval’s much-lauded Linga Franca, Hong Khaou’s tender second feature Monsoon, and Oliver Ducastel and Jacques Martineau’s dark and complicated Don’t Look Down. Now, just a year later, there are simply fewer films rearing and ready to go with the future of the distribution and the industry at large in flux.

It may seem that, from my summations here, a lot of the entries into this year’s Flare festival were a little lacking, especially compared with last year, and that might not be entirely fair. I have to disclose my bias: as a queer person, I’m positioned to want a lot from my LGBTQ+ and Queer Cinema. That means that, when it disappoints, it really disappoints. I feel, when they aren’t perfect, like that famous clip of Tyra Banks: “I was rooting for you, we were all rooting for you!” I’m sure the films I’ve discussed here will find their audience; there are many LGBTQ+ viewers out there desperate for something new who will see a glimpse of themselves within them. All of us are looking to the future; the future of film, festivals, and queer cinema. All of us want the best.

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On Kathryn Hahn

1 Comment

Comments are closed.