There are two types of people: those who enjoyed their time at high school and those who didn’t. The former is easy to find as they extol the virtues of the good ol’ days and how they wish they could go back. When they get together, they pass stories around, like the joints, they once smoked at parties, while sitting at beer-soaked picnic tables in pub gardens. They talk about the time they made the science teacher cry, the parties at which La Roux’s “In For The Kill” was played in between wordless dubstep on some rich boys’ DJ decks. They revel in a time before things got tough, before taxes and responsibility when things were easier. Then, there is the other type of person, who, like me, sits firmly in the I-couldn’t-think-of-anything-worse camp. For us, high school was a constant negotiation, a continued policing of our gayness, our fatness, our body, or our attitude. It was not a place where we learned that things might get better; just a place where we simply hoped things would not get worse.

We heard stories that, at college, it would be different, and so we spent our time waiting to get out. So when we hear those people ask, “Wouldn’t you go back if you could?” we retort with a simple; “Why would you want to?”

In the past few weeks, for reasons that weren’t at the time clear, I started watching a lot of television made for teenagers and tried to consider the high school experience I might have had today. On Disney+, Love, Victor has been premiering a new episode weekly, and, after repeatedly listening to ‘Drivers Licence’ on my daily walks, I checked out Olivia Rodrigo’s show on the streamer too, the ridiculously named High School Musical: The Musical: The Series. The former is a spin-off from 2018’s Love, Simon – a film I have a mixed relationship with – and the latter a spin-off of the wildly successful High School Musical franchise of my youth, sans Zac Efron’s boy-next-door charm. Neither show is particularly good, but neither is outrageously bad. And yet, I have become strangely addicted to both.

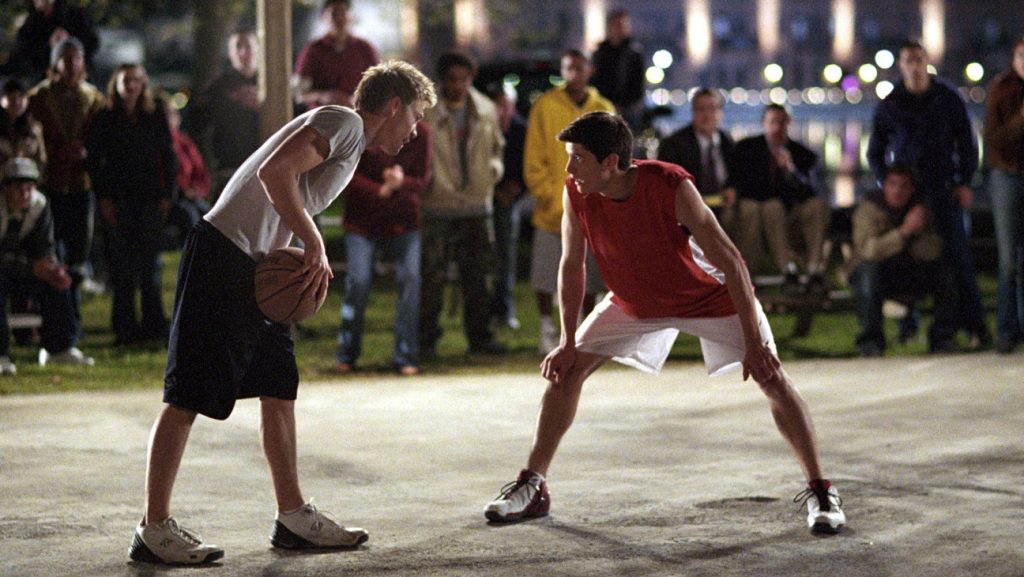

This is not new for me. During my high school years, I would go home and watch the experience I wanted for myself play out on television. I religiously watched the melodramas of beautiful actors in their mid-twenties pretending to be seventeen on shows like 90210, The O.C., Gossip Girl, and, my all-time favourite, One Tree Hill. The latter (whose theme-tune was my ringtone from 2010-2012) followed a group of teens in the fictional town of Tree Hill, North Carolina. The central storyline focused on Nathan and Lucas Scott, two half-brothers locked in a bitter rivalry as both tried to be the star basketball player for their team, the Tree Hill Ravens. While Nathan had his upsides, Lucas was, for me, the ideal man. Played by Chad Michael Murray, he was, of course, gorgeous, but he was also sensitive, and his dream was to become a writer. He read Hemingway and Salinger whilst he wrestled with his abandonment issues. He was the furthest thing from the boys at my school, who may well have had abandonment issues too, but funnelled them into shouting faggot across the school field instead of into a pursuit of the great American novel.

As I got a little older, aching to finish my GCSEs and get out, E4’s Skins became appointment viewing for me and my classmates. The character of Maxxie Oliver, the openly gay member of the wild and raucous central group, became my obsession. Maxxie not only had more to say than the “gay best friends” in every teen movie, but he also had a sexy encounter with a friend whilst on a trip to Russia, he had a female stalker that refused to accept his gayness, and he ended up snogging his skinhead bully after a woodland rave, rolling around on the mossy forest floor. He was more himself than I could ever be.

If Lucas Scott was the man I wanted, then Maxxie was the man I wanted to be. He was, of course, openly gay (something I kind of was) and actively sexual (something I definitely wasn’t). I saw his gung-ho nature, his sexual freedom, and thought one day, that would be me. Looking back, as important as Maxxie might have been to me, he was almost mythic, in that I’m not sure teens like him actually existed outside of drug-filled shows like Skins. At least, not where I grew up.

Those shows, then, were aspirational for my teenage self; they showed roadmaps for leaving school, for figuring out the kind of boy I liked, for how to approach sex. These new shows are that for a new generation, only they’re a lot gayer. Love, Victor is about a gay kid figuring out his sexuality – something that never happened on One Tree Hill – and High School Musical: The Musical: The Series features some tender, if sanitised moments, of young gay love. Now, aged twenty-seven, I no longer need the affirmation these shows provide, no longer think of sex and men as aspirational ideas but rather as practical and routine problems. So why am I watching them?

Last week, whilst I sat in the park with a friend, I wondered if I had been born both too late and too early. Coming of age in the early 2000s, the lingering effects of Section 28 peppered my high school experience and the onset of the “It Gets Better” movement was yet to arrive. I was too late for radical queer politics. Instead, it was all marriage and the military. But I was also too early to go to a high school that had a club for gay students, in which teenage queers had relationships. I was too early for shows that centred a teenage experience similar to mine. Two of my friends have younger brothers who are gay, and when they talk about them, I’m always struck by how self-assured they seem, especially sexually. They didn’t think that gay sex was some colossal mystery. They didn’t grow up thinking queer life was reserved for the future, for college or university. As the characters in these shows do, they believed that queerness not only exists in high school but is acknowledged.

In her 2009 book The Queer Child, Kathryn Bond Stockton describes queer adolescence as like “growing up sideways”. Queer kids didn’t share the linear trajectory of their straight peers, and they knew it. Instead, she describes growing sideways as a mode of “irregular growth involving odd lingerings, wayward paths, and fertile delays.” Perhaps that is no longer the case. I grew sideward, but the kids on these shows don’t appear to be doing the same. They aren’t wholly as secure as their straight counterparts; Victor, for example, spends the entire first season (which concluded this past Friday) wracked with panic about his sexuality. Still, Victor feels more like a real teenager than Maxxie ever did.

A few years ago, I watched a clip of Gloria Steinem on Oprah in which she said it is never too late to have a happy childhood, and her way of filling the gaps left by her parents was to write a list of all the things she didn’t have and use that as a list of things she needed to do for herself: “Going back to the past and giving yourself in the present, in an activist’s sense, what you realised that you lacked. The unconscious is timeless, stored in those brain cells is your entire childhood, and you can re-enter them and change it.“

It’s possible I’ve become obsessed with these shows because I have trouble reconciling the experience I feel I was robbed of. When I watched those shows as a teenager, I saw these people whose lives were filled with drama and emotion, whose love lives extended into complicated and tumultuous territory. I thought, rightly or wrongly, that that was what it was like to be a teenager and, while for me it wasn’t, for the kids on these shows now, it is. I’m trying to change my relationship with those years, to live a different version of them. Maybe now, when people ask if I would go back to my school days, my answer wouldn’t be why would I want to, but rather, I don’t need to.

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On Needle Drops