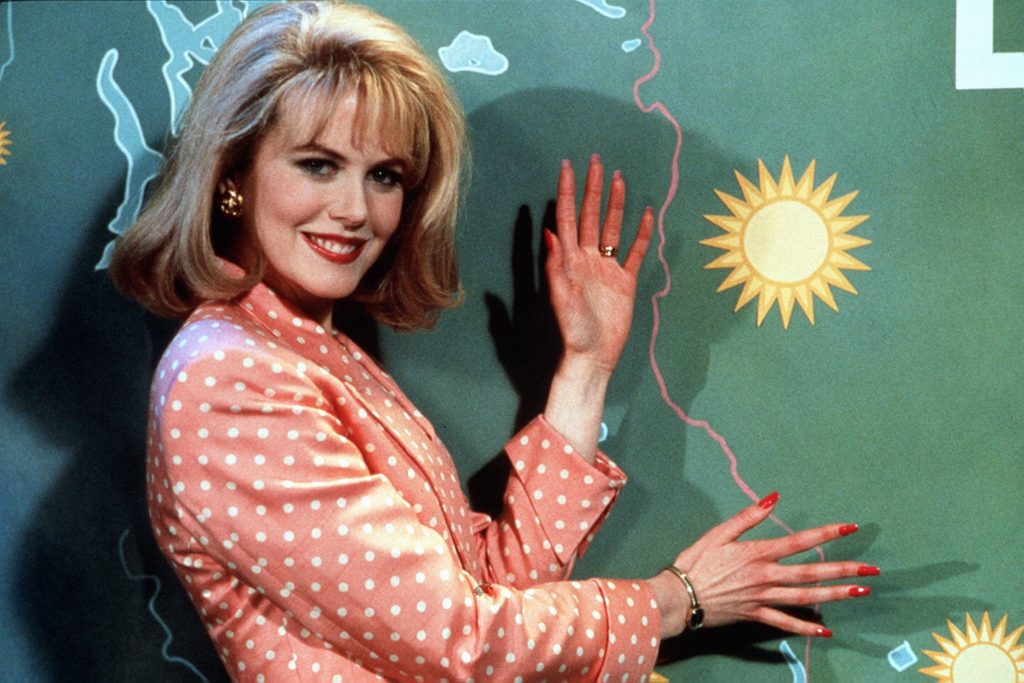

If you, like me, are just desperate to feel something other than existential dread during Lockdown 2: Back in the Habit, then you’ve likely been watching The Undoing. If you haven’t, the twisty thriller, based on a book by Jean Hanff Korelitz, stars Nicole Kidman and Hugh Grant as a wealthy New York couple caught up in a horrific murder case. Not only is it providing some level of escapism, with its lavish Manhattan apartments, dramatic plot twists, and its lack of social distancing (it was filmed pre-pandemic), but is also airing one episode a week, reminding me that time is indeed passing and we are not stuck in some stagnant version of hell. Instead, each week is marked by an hour of Nicole Kidman doing what she does best; wearing wigs and acting everyone off the screen.

As a queer person, I routinely discuss how much I love actresses. From Laura Dern to Dakota Johnson, Holly Hunter to Kristen Stewart I love the work of women (I am basically that clip of Saorise Ronon saying “women” emphatically) but Kidman, has always been a point of specific interest. The first time I remember seeing a Nicole Kidman film was likely Moulin Rouge when I was around thirteen. My high school, quite inappropriately, decided to adapt the movie for the stage as that year’s school play (long before the Broadway version existed) and I watched the film over and over during rehearsals. Not so much because I had a big role (I was in the chorus and had three dance numbers which I slayed) but because I became obsessed with Kidman as Satine, a courtesan dreaming of a life elsewhere. I used to listen to her version of ‘One Day I’ll Fly Away; as if it applied to my own teenage existence on frosty Winter mornings as I wandered to school. What I didn’t realise at the time was that Moulin Rouge was also a crucial film in the emancipation of Kidman.

When Kidman first broke into Hollywood in the late nineties, she was primarily seen as Tom Cruise’s girlfriend. Despite success with the thriller Dead Calm, Cruise was the biggest movie star in the world, and ultimately his overall star power consumed Kidman too. They worked together in films like Days of Thunder, Far and Away, and Eyes Wide Shut – all of which gained attention for starring the real-life couple. Her other films, well-reviewed but lacking impact (like Gus Van Sant’s To Die For or Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady) flew mostly under the radar. At the same time, her more significant blockbuster roles (in Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever) were often written off as campy. Her move, from a respected indie actress to a major movie star, facilitated by her marriage to Cruise, provided both pros and cons. As Ingrid Sischy wrote in a 2002 profile of Kidman, “She went from being an actress who had begun to taste success—and who had always insisted on living on her own, even during her various romances—to a woman inside the engine of the Hollywood machine.”

When Kidman and Cruise divorced, the tabloids raised the question of who would “win” the break-up. Would it be Cruise? The megastar with millions of adoring fans and a proven track record in Hollywood. Or would it be Kidman? An Australian actress whose highest-profile roles were directly connected with her husband. The answer seemed obvious.

In early 2001, the couple announced their divorce, and later that year, in May, Moulin Rouge premiered at the Cannes film festival. The film went on to be nominated for eight academy awards the following year including a Best Actress nod for Kidman. That year she lost to Halle Berry – a historic win of its own – but this nomination cemented her position in Hollywood moving forward. Not only was she well-reviewed and Oscar-nominated but the film made $179.2 million at the box office, more than doubling its original budget. When this was put together with The Others, which came out a few months after Moulin Rouge and was also a critical and financial hit, it was clear Kidman was more than the sum of her celebrity marriage.

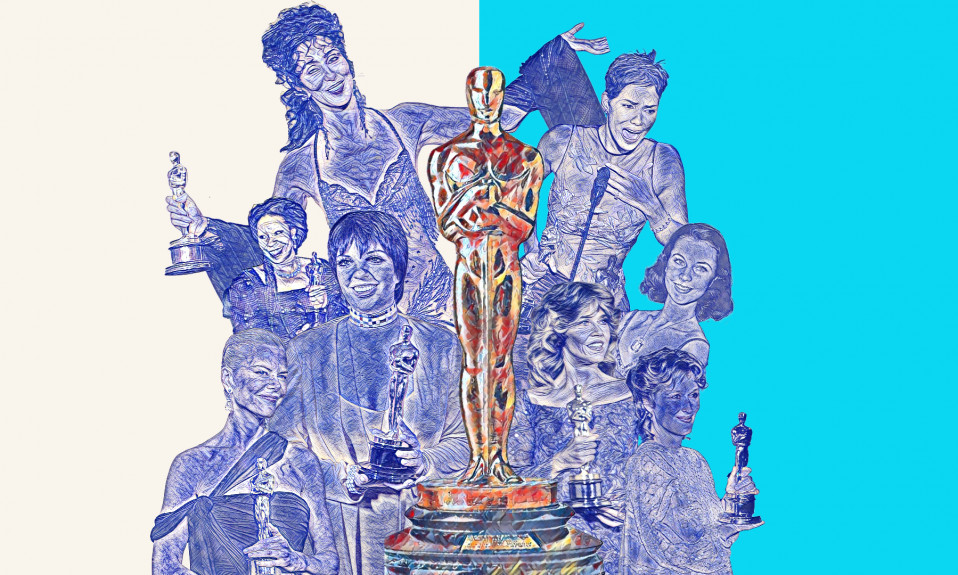

A few years ago, a friend asked me if Nicole Kidman had ever won an Oscar. “She’s been nominated four times and won once,’ I said, surprised at how quickly that knowledge came to my mind. My friend followed up, asking which films she’d been nominated for. “In chronological order,” I said, “Moulin Rouge, The Hours (which she won for), Rabbit Hole, and Lion.” Again, I hadn’t realised I’d absorbed so much “kidmanformation” (I just coined this, we’ll see if it catches on) in my everyday life. Of course, my daily life (as a queer movie person that watches Oscar acceptance speeches on YouTube in my spare time) is not the same as everyone else’s.

Her performance as Virginia Woolf in The Hours is one of my all-time favourite Kidman performances. Spurred on by the rawness of a significant public break-up, Kidman embodied the writer who was on the brink of suicide. She captured a woman lost and struggling with how to be and how to act. She transformed herself physically too, something Kidman regularly does but often doesn’t get much credit for, proving that she was an actress to reckon with. Despite the Oscar win, her public persona was somewhat confused. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, Kidman was written off by many and was often cited as having a “comeback” any time she made something critics liked. In a 2017 article for Buzzfeed, Anne Helen Petersen wrote,

Kidman — like Witherspoon and Dern, like Stewart and Woodley, like so many actresses, of seemingly every age, who aren’t named Meryl Streep — has to prove herself as more than the sum of her pretty parts every time she comes onscreen.

Alan Helen Petersen, Buzzfeed

Post-The Hours, Kidman straddled arthouse movies and big blockbusters. She had critical hits and major flops; she moved into producing, and through her work on Big Little Lies she made a huge impact on TV too. She has worked with Yorgos Lanthimos, Sofia Coppola, Park Chan-Wook, Lars Von Trier, Nora Ephron, and Noah Baumbach, to name a few. She routinely takes risks and jumps between genres, but isn’t afraid of a big pay check gig – like Aquaman – either. She is the modern movie star who understands the requirements of Hollywood (one-for-me-and-one-for-you) but plays that so keenly to her advantage that it never feels like she’s selling out. To put it plainly, Kidman is the GOAT and we’re lucky that we’re alive to see her thrive.

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On Sex Scenes