Once, walking down Kilburn High Road in 2017, I surprised myself by knowing all of the Oscar nominations Nicole Kidman had received. My roommate and I had watched Eyes Wide Shut the night before and discussed it as we headed out to run errands on a warm Saturday in spring. Casually, my friend asked if Kidman had ever won an Oscar and, without hesitation, I reeled off the four films she’d been nominated for: Moulin Rouge, The Hours, Rabbit Hole, and Lion. The film names came from somewhere deep within my brain, and it required no effort to conjure them. As we passed the market and walked toward the tube station, I spoke about Kidman and the Oscars. I knew she’d won for Leading Actress in The Hours, but of the three women in the film, she had the least screen time. I knew that when her name was called, the presenter, Denzel Washington, referenced the fake nose she wore in the movie to embody Virginia Woolf better. I knew her first nomination a few years before her win had come in the wake of a highly publicised divorce from Tom Cruise and had acted as a signifier that Kidman was far more than Cruise’s wife. I wasn’t sure how I knew all this, but I did.

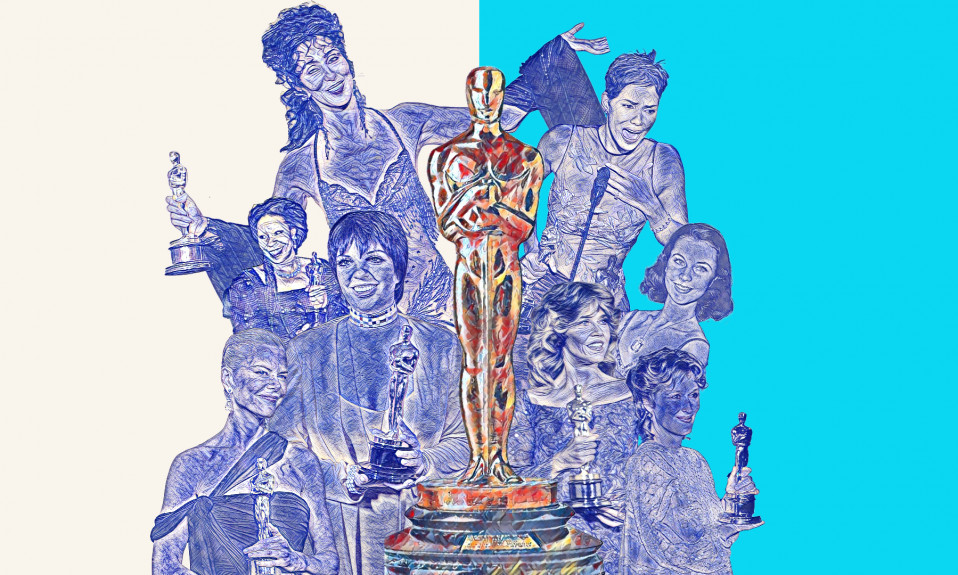

It occurred to me later that I’d absorbed a lot of Oscars information as a teenager when I spent my time watching acceptance speeches on YouTube and scrolling through the Trivia section on IMDb whenever I watched a movie. I also knew that the wealth of my knowledge-focused heavily on women because, as in most art forms, their work interested me more. The Oscars led me to some of that work, to the kinds of films I wasn’t aware of as a child, the type of films that played against the big blockbuster movies of my youth and instead featured women who did more than scream and ask the male lead what to do. This meant I’d go and see movies like Rachel Getting Married, An Education, or Blue Valentine with the money I got from my first job; films that introduced me to a different kind of filmmaking. I also used the Oscars as a basecamp for movie history by scrolling back through the lists of previous Oscar winners and becoming obsessed with Kathrine Hepburn, Judy Garland, Deborah Kerr, Barbra Streisand and many others, all of whom were women who had their own history of being overlooked or celebrated by the Academy.

It seemed, however, that any Oscar titbits I might learn mainly were seen as useless information or, at best, a party trick doled out to impress people for a few minutes before they became bored when I tried to discuss the subject further. I knew an older gay man who could list every Best Picture winner in order after a few drinks at the pub and thought, maybe one day, I’d do the same with the actresses who had won but, beyond that, it wouldn’t be very useful. Occasionally, when I watched a film with my housemates, one would point and ask if an actor in the movie we were watching had ever won an Oscar. I could say yes or no and, in the cases of actresses, had a good idea about what they’d won for. Or, like had happened with Kidman that Saturday morning, a few small opportunities would appear from nowhere, and I’d be in my element before the conversation inevitably moved on.

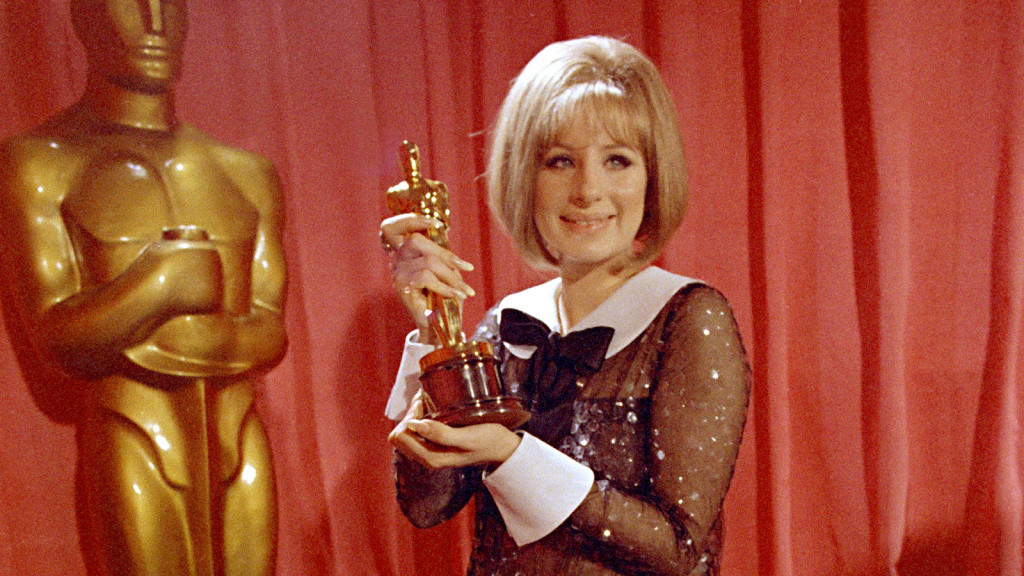

Some years after I summoned Kidman’s filmography as if through divine intervention, I was scrolling through YouTube, likely watching my favourite Best Actress speeches, when I came across a video dedicated to the tie between Barbra Streisand and Katherine Hepburn in 1969. This was one of the first Oscar stories I got wrapped up in after I began looking at its history. It featured two actresses I loved, unpacked the myths that had sprung up around that year, and, beyond all that, I was obsessed with the sheer black outfit Streisand wore to the ceremony. I clicked the video immediately, and at over fifteen minutes, the video deepened my understanding of that moment and my knowledge of two actresses I loved.

The video was uploaded by Be Kind Rewind, a channel dedicated to essayistic deep-dives into actresses who have won Oscars. As a standard format, each video focused on a particular Best Actress winner in a specific year by considering the narrative created around the winner, the other nominees, the cultural context that led to each woman accepting the golden statuette, and the socio-political implications behind Hollywood’s biggest night. After I finished the first video, I burnt through all the analytical, insightful and well-researched video essays they’d uploaded so far and eagerly awaited new ones.

As the channel grew, it expanded into videos that moved away from the Oscars, but its focus remained on women. In 2018, the channel released a video examining the differences between the many versions of A Star is Born, looking specifically at the role of ‘The Star’ and how it differed from Janet Gaynor to Judy Garland, to Streisand, and then Lady Gaga. They released “hot takes” on the recent award wins, particularly the 2019 race when Olivia Coleman won over Glenn Close, and an excellent essay on Madonna’s filmic references within her many music videos. There were lengthy and nuanced discussions of the Academy’s controversies, too. There was a set of two excellent semi-linked videos on #OscarsSoWhite. The first focused on Halle Berry’s historic win in 2001, and the second on the poor representation of Asian and Asian American women at the Oscars throughout history. In other videos, such as those dedicated to Kidman and Gwyneth Paltrow, they considered the Harvey Weinstein of it all, a figure that looms large in any discussion of movies from the nineties and early noughties. In essence, the videos not only gave reverence to the women and the performances at their centre but connected them to a broader context in a way that fought back against the frivolity and in-built misogyny that coloured discussions about them in the past. So often, the performances nominated for Best Actress do not come from films nominated for Best Picture, which leads to Be Kind Rewind’s central message: that art made by, for, or featuring women should not be devalued or considered less than on this basis alone.

For over a decade now, the Academy has expanded the Best Picture category from five to a possible ten, with the actual number varying each year depending on the number of votes it receives. In a 2017 article for Vanity Fair, Daniel Joyaux looked at the correlation between Best Picture and the Leading acting categories. Between 2011 and 2017, 30 actors and 30 actresses were nominated for leading roles, but as Joyaux notes, “while 21 of those best-actor performances came in films that were also nominated for best picture, only 12 best-actress performances came from best-picture nominees.” In focusing on Best Actress wins, Be Kind Rewind gives time and space to often ignored or undervalued films. This, more often than not, is because the Academy, and the film industry at large, have shaped perceptions around what “prestige” means, about what “good” means, and it almost exclusively applies to male-led films.

“What is considered good or important cinema?” the narrator asks in their video on the 2020 Oscars race. “Thankfully, the Academy isn’t the only body attempting to answer that question, and their decisions are rarely considered sacrosanct.” So why are we drawn to them? The Oscars’ longevity and their centrality within the industry imply a sense of status, but that centrality also makes them a prime place to start for the cultural evaluation found in Be Kind Rewind’s videos. Part of loving the Oscars or being interested in their past is to acknowledge the Academy’s flaws. Increasingly, year by year, those who grew to love the Oscars when we were younger find ourselves increasingly annoyed that performances or movies that make waves or are considered significant are ignored. This, for me, was best encapsulated in this year’s ceremony, when not a single person I wanted to win took home an award (and other actors who I think deserved the top prize, like Renate Reinsve in The Worst Person in the World, weren’t even nominated).

In a recent interview with W, Izzy, the creator of Be Kind Rewind – who told the magazine she would like to remain “semi-incognito” – described the channel as a place for people who love classic cinema, and particularly the women that populate it, to come together. “There aren’t too many places to congregate and meet people who are interested in those same things, so the internet opened up the floodgates”, she said. “When I declared loudly online that this was what I loved talking about, it allowed others to find me.” This echoes the general notion of the good that the internet can do; it connects people. It is perhaps helpful to remind ourselves of this as being online is becoming increasingly hellish. There are corners of the web that offer people the chance to be passionate about things and for others to engage with that passion, to meet that enthusiasm head-on. For me, Be Kind Rewind’s YouTube channel is one of them.

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On Nicole Kidman