When I was fourteen, my ringtone, for about six months, was Julia Styles’ poem from the end of 10 Things I Hate About You. Any time I got a call or a text it would buzz, and Styles’ voice would go from apathetic to emotional. It would crack as the emotion swelled in, and then I’d answer. I open with this tidbit as an example of the vice-like grip movies like 10 Things I Hate About You held over my adolescence. I devoured these movies and watched them over and over without realising there was a single thread that they all had in common: they were based on classic literature. Whether I was forming feelings over Ryan Phillippe’s bare ass in Cruel Intentions, becoming deeply involved in the gender-bending high-jinks at the centre of She’s The Man, or quoting lines from Easy A word-for-word with friends, all these movies were exploring and unpacking issues written about centuries before.

Earlier this week, I thought about these movies when Hulu released the trailer for their upcoming queer rom-com Fire Island. The film, due for release in the US on 3rd June, transposes the action of Jane Austen’s classic novel Pride and Prejudice into a queer space, the Bennets are no longer four middle-class sisters in the south of England but, instead, a group of gay men on vacation at the iconic summer spot. The subject of Austen’s novel and its many faithful adaptions seem perfectly primed for a queer retelling, not just because the words ‘pride’ and ‘prejudice’ have a strong connection with contemporary queerness but because its themes and ideas seem like a perfect fit with the image-obsessed world of contemporary gay men.

Fire Island stars comedian Joel Kim Booster as a version of Elizabeth Bennett, a former waiter who ends up quarrelling with Conrad Ricamora’s rigid and awkward Darcy stand-in. SNL’s Bowen Yang becomes a version of Jane Bennett, the close friend and confidant who falls for and likely has their heartbroken by, a handsome doctor he meets at a party. Austen’s themes of social status and the strength of family units fit naturally here, only the lavish Pemberley becomes a glass-fronted beach house, and the family is a chosen one rather than blood. In contemporary queer politics, too, there has been a significant focus on status, social and financially, amongst gay men regarding their views on assimilation, approaches to sex, and the privilege awarded to wealthier gays, who often get the most attention in mainstream culture. It’s interesting to note that Fire Island features a distinctly diverse cast, both in terms of race and physique. This shouldn’t be radical but, in Hollywood, gay men are almost always white and adorned with rippling pectorals.

Pride and Prejudice, of course, has been modernised before in the form of Bridget Jones. Renee Zelwegger’s bumbling publishing assistant-turned-journalist gets caught in a love triangle between the sensible and repressed lawyer Mark Darcy and the cheeky yet morally suspect Daniel Clever, which mirrors Elizabeth’s position when choosing between Mr Darcy and George Wickham. There have been many faithful adaptations, including the landmark BBC TV series, versions made for Bollywood, and the exceptionally brilliant 2005 version by Joe Wright, starring Keira Knightly and Matthew McFadden pre-global domination thanks to his role in Succession. It would be remiss not to mention that Pride and Prejudice and Austen have significant name recognition. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone in the west who hasn’t at least heard of it, and because of this, it’s not difficult to imagine studio heads and financiers thinking about them in the way they think about Spider-Man or franchises about any kind of man. But there’s clearly something in the story, thematically, which draws writers and filmmakers to it repeatedly.

The wonder in movies like Fire Island or Bridget Jones’s Diary is precisely in the way they’re updated. It might sound simple, or even obvious, to say that what’s so appealing about them is how they take classic ideas and modernise them, but doing so creates a chain of sorts, whether we’re aware of it or not. It connects past and present and deepens the universality of their themes. The greatest example of this, to my mind, is Cruel Intentions. Released in 1999 to some substantial controversy, the film is an update of the French novel from 1792, Les Liaisons Dangereuses. It’s a book filled with scheming and dissections of gender relations amongst the nobility in 18th century France and, a decade before its teenifcation, it was made into an Oscar-winning period drama starring Glenn Close and John Malkovich. Cruel Intentions moves the action to modern-day New York and fills its cast with wealthy socialites obsessed with their reputation and image. Katherine, a version of the Marquise de Merteuil, is a popular girl at an Upper East Side private school. Her image is well-curated, relying on supposed purity and moral superiority. In private, she is the opposite. She seeks out and enjoys sex and revels in manipulating other people’s lives. Her position in society hinges on this façade, and, by the film’s close, those around her take satisfaction in her downfall as her stepbrother, the equally vile and perhaps worse Sebastian, is valorised.

Cruel Intentions is an inditement of the double standard inherent between men and women in the nineties as seen through the lens of several self-absorbed rich folks. Sebastian is brash, egotistical and loud. To him, women are dispensable, often games that he can partake in until he gets bored. He relishes in taking their purity and values his reputation as the kind of man from whom no woman is safe. As such, women fall at his feet. Katherine is his equal. She is desirable and confident. She’s sexually experienced but is routinely passed over by men for women who are virginal and innocent. Her experience as a woman is not valued and is not something Katherine can openly discuss. A video essay for The Take released a few weeks ago suggests that these dynamics make Cruel Intentions the clever, dark and lasting movie it is because Katherine’s character is a complex antagonist that we all find so captivating.

Unfortunately, they don’t make films like Cruel Intentions anymore. Aside from Fire Island and Netflix’s 2019 film The Half of It, a modern queer take on Cyrano de Bergerac, they don’t seem to be in fashion. At least, not as much as they were in the late nineties and early noughties when classic work, particularly the plays of Shakespeare, were ripe for the pickings. Now? Not so much.

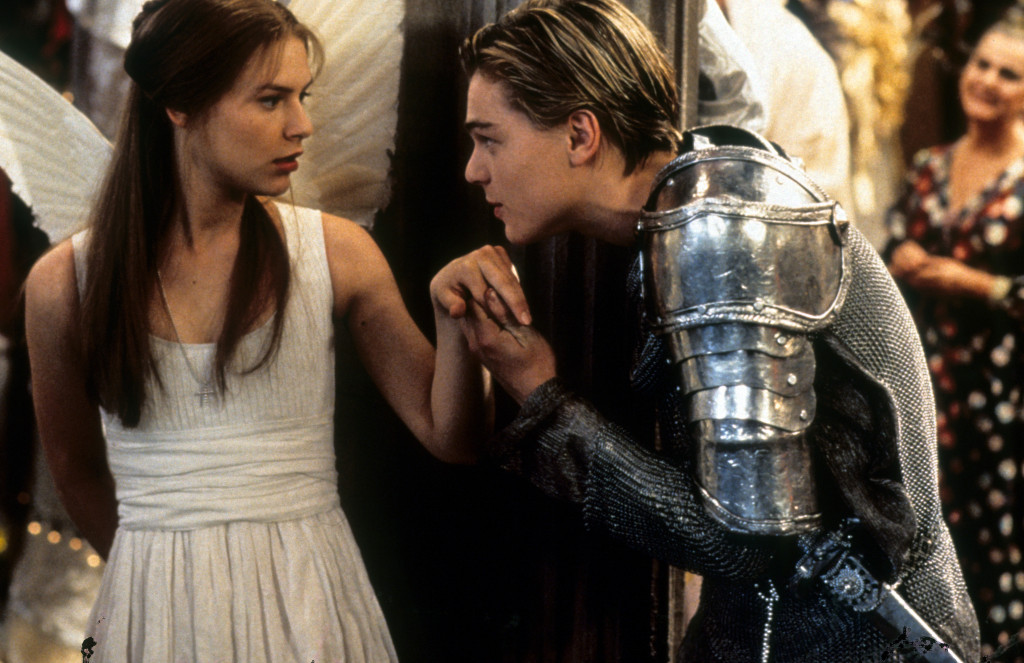

On her YouTube channel, Broey Deschanel breaks down the reasons for this in her video on Baz Luhrmann’s campy, MTV-inspired fever dream Romeo + Juliet. The fact movies like Romeo + Juliet, or any of the ones mentioned above, take what is typically considered high culture (Shakespeare, 18th-century novels, classic plays) and turn them into accessible, fun and modern interpretations goes against the cultural ethos; that which is exclusive and potentially harder to understand doesn’t belong to the masses. Instead, by transposing the action of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night to a private school in America, modernising the dialogue, swapping out the period-accurate costumes for Amanda Bynes in make-up and a young Channing Tatum in sportswear, or placing The Taming of the Shrew amid nineties feminism, the themes and ideas of the play become accessible to teens. Moreover, they can be updated along the lines of gender and sexuality. For example, in 10 Things I Hate About You, Kat Stratford doesn’t need to deliver Katherine’s lengthy monologue that comes toward the end of Shakespeare’s play, one that attests women should be subservient to men, one that proves she’s truly been tamed. Instead, she can write a poem claiming she misses the man she loves, and they can kiss in the car park while nineties pop-rock plays in the background, but we get a sense that Kat has met her equal, not her master.

Nothing defines culture more than those who try to gatekeep. Cultural institutions assign value to certain things, often enjoyed by the middle classes and usually requiring further education and money to consume. They panic that if everyone has access to these stories, they’ll lose value, and then what will they have left to make them feel superior? This, of course, is not the case. I love classic literature and, at times, I even love Shakespeare, but throughout my teens, my access to those stories was through modernised adaptations. I didn’t grow up in a house filled with books. I wasn’t introduced to lengthy high-brow film adaptations of Shakespeare. Instead, I saw the films that dispensed with the poncey finery, that allowed people to see the story anew. It seems a shame that filmmakers seem less interested in providing this in 2022. Here’s hoping Fire Island bucks the trend and ushers in a swell of new adaptations.

Also Read: Too Awkward For Love: Understanding the British Rom-Com