A few weeks ago, I started getting the emails; would my dad like a new BBQ, 50% off a takeaway meal at our local restaurant, a book on the history of the Second World War, or some fancy IPAs selected just for him this Father’s Day. Each new email that popped into my inbox like a relentless buzzing fly irked me, my finger swatting to delete each one with rapid fury.

My dad is dead and has been for nine years. As I write this, it is hard to believe it’s been nearly a decade while, at the same time, totally plausible, given that it feels like a lifetime ago since he was hospitalised and died one cold night in January 2012. In the nine years since, I’ve looked for him, for us, in film and on TV and, around this time of year, around days like today, I do it more regularly. Still, I haven’t ever seen the kind of relationship my dad and I had. I see echoes of it, hauntings of its complexity, but never exact replicas.

In Mark Rydell’s 1981 film On Golden Pond, for example, Chelsea (Jane Fonda) feels distant from her father, always suspecting he wanted a son. When she needs to go away for the summer, Chelsea leaves her own son with her parents at their lake house in New England. When she returns a few weeks later, she notices that her thirteen-year-old and her father, Norman (played by Fonda’s real-life father, Henry Fonda), have formed a strong bond, one she was never able to achieve with Norman herself. In a scene towards the end of the film, Chelsea confronts her father as he sits on his boat, tied to a small jetty. “Maybe you and I should have the kind of relationship we’re supposed to have,” she tells him, nervously, by the water’s edge. When Norman responds coldly, with a jibe about her inclusion in his will, Chelsea storms into the water. “I want to be your friend,” she tells him tearfully and reaches for his arm. “If this means you’ll come around more often, it will mean a lot to your mother,” Norman says before the two move the conversation on, both hoping that what they’re not saying is resonating with the other.

When I watched it for the first time a few years ago, I welled up at this scene. Even more so when I realised that Jane Fonda, who produced the film as a way to get closer to her father, improvised reaching out for him – an act she felt she needed to do in the moment. It reminded me of the morning after I came out to my dad. I had gotten too drunk at a friend’s 17th birthday party and had been picked up around 9pm because I was being sick on the street. At home, between chundering into the toilet and resting my head on the cold plastic seat for relief, I told him I liked men. I don’t remember doing this; it’s all facts filled in by my friends who were present. The following day, in a strange conversation I remember with an awkward clarity, he realised I didn’t remember anything, and so he rested his hand on my shoulder and never spoke of it again.

Growing up as a queer kid when I did often meant that these types of gaps opened up between my dad and me. When I had my first crush or my first kiss with a boy at a party, I couldn’t tell him. I couldn’t talk to him about the things other boys said to me at school, nor the things I hoped for in my life. I was eighteen when he died, and I’ve spent the time since trying to reconcile what was in those silences. How did those gaps affect us? Like Chelsea, I spent a lot of my youth wondering if I was the child he wanted, which wasn’t helped by the fact I have a brother who, it seemed to me at least, was very clearly the “right kind” of son. In actuality, that sense of distance opened up because there were huge parts of myself I couldn’t share, and which he didn’t ask about.

What I see more regularly, though, are examples of what it’s like to lose a father. Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester by the Sea covers the expanse of time between Patrick’s father’s death during a cold Bostonian winter, with his body frozen in the morgue to preserve it, until the warmer months when the ground thaws enough to bury him. During this time, Patrick (Lucas Hedges) lives with his uncle (Casey Affleck), and one night has a breakdown when frozen steaks fall from the freezer as he opens it. Scrambling to put them back, he knocks his head on the freezer door, then tries to slam it shut, but it refuses. His breath quickens, and he starts to cry. “I just don’t like him being in the freezer,” he tells his uncle, and it becomes clear we’re observing one of the strange manifestations of grief, in which seemingly innocuous things cause devastation.

Recently, my shower broke. The button jammed, meaning I couldn’t turn it on, and I found myself crying, trying to stop myself from pulling the whole thing off the wall, in what seemed like a totally unreasonable response. I texted a friend, telling her what had happened, and she, very kindly, offered to ask her dad if he could have a look at it, and I realised that my own dad would not be able to. It didn’t matter that my dad was not particularly handy in that respect; the fact I couldn’t call him for help like she could drove me to near insanity. Perhaps it would have been helpful to use the opportunity to try and learn how to fix it myself but it is still out of use as we speak.

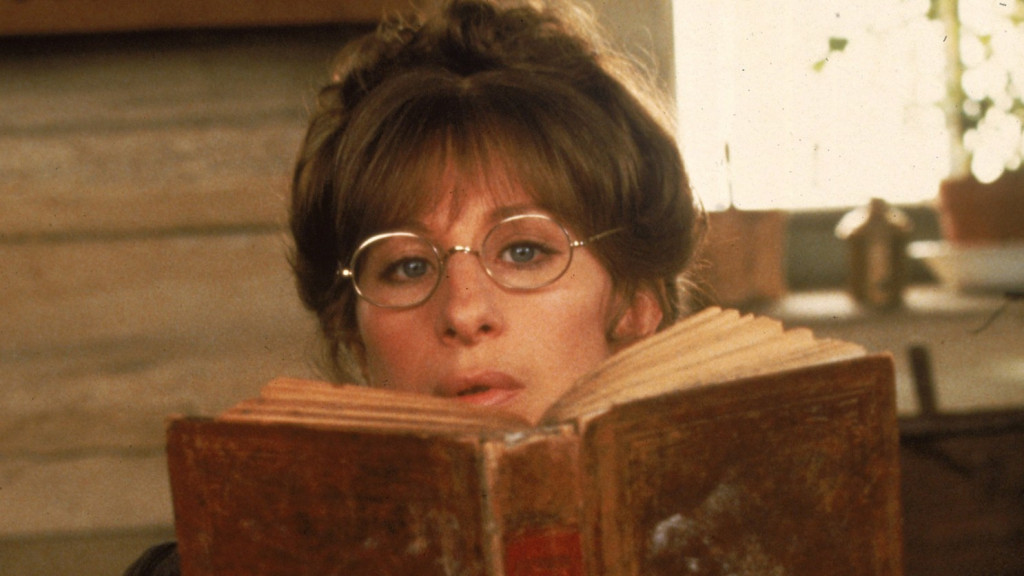

In Barbra Streisand’s musical magnum-opus Yentl, however, we see her father’s death as a driving force in her life. Set in 18th century Poland, Yentl (Streisand) is a young unmarried Jewish woman who strives for more. She is desperate to get an education, and her father secretly teaches her about the Talmud at night. When he dies, however, Yentl is unshackled, not just from her father’s physical presence but from the one person that stoked her intellect and understood her ambitions, and so she runs away. Disguising herself as a boy and taking on her deceased brother’s name, she enters a Yeshiva and continues to learn.

The music in Yentl, which Streisand co-wrote, is designed to sound like the twelve lessons of the Talmud in which one follows the other. In this sense, both melodically and lyrically, the songs blend to create a gateway into Yentl’s mind. In the second song, “Papa, Can You Hear Me’’, Yentl, having just run away, speaks to her father in heaven. She lights a candle as if he can see her, as if he is watching over the decisions she’s making. She asks for forgiveness if she is falling short of what he expected.

In the closing lines to the rousing song, the excellent “A Piece of Sky”, Yentl speaks directly to her father again: “Papa, I can hear you / Papa, I can see you / Papa, I can feel you / Papa, watch me fly”. Sung from an ocean liner as she travels to America, she is finally branching out further than before, leaving behind the regimes that trapped her, and knowing her father would be proud.

These closing scenes on the boat were shot on the River Mersey in the 1980s, with Liverpudlian extras making up the other passengers on the ship. When I look this up online, I can see grainy photos of these men and women, all dressed up in period costumes, with the Albert Dock and Liverpool waterfront in the background. My dad grew up in Liverpool, I went to university there, and the city feels like something that connects us. As a kid, we used to drive down that dock road on our way to visit my grandma, emerging from the tunnel to see the Liver Building, its statuesque birds protecting the city, backlit by a pink sky. Often caught in traffic, we would edge slowly along and I would look out at the water where, years before, unbeknownst to me at the time, Streisand had sung, and I would ask my dad questions. Did he think he would be much good in a car chase? When did he have his first girlfriend? What did the city used to be like?

Yentl’s words, echoing out across the Mersey, were not too dissimilar to the things I wondered while I was living in Liverpool after he died, as I grew into myself. These are things I still wonder now, as a queerer and more self-assured version of myself than he ever saw. I expect I’ll still be wondering about this next Father’s Day, too.

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On Friendship