‘The only thing my dad gave me that was worth anything was pain and you want to take that away from me,’ says Otis, a former child actor who is currently attending court-ordered rehab. He is in the process of therapy, something that is being recorded to prove to the courts he is recovering and Honey Boy was written from that exact place.

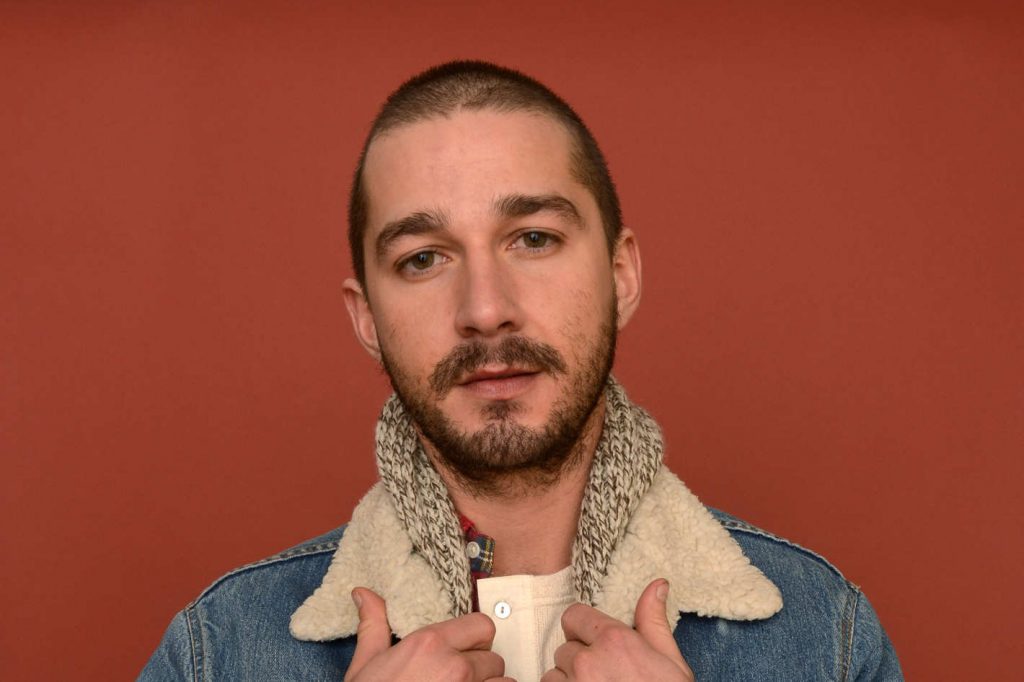

Shia LaBeouf, once a famed child actor and now more commonly known for his performance art and various arrests, wrote the first draft of the script from rehab where he sent it to Alma Har’el, a friend and confidant (who would later become the film’s director). It was an unfinished draft, born from LaBeouf’s therapy sessions, and once LeBeouf was out of rehab the two finished it together. While this might sound like the kind of Hollywood vanity project fuelled by ego that you might expect from someone in LaBeouf’s position, it’s couldn’t be further from it. It’s tender, disarming, sympathetic, hypnotising, and raw.

The film follows an adult Otis (Lucas Hedges) as he examines his past and his relationship with his father after being diagnosed with PTSD from his childhood. Through flashbacks, we see a younger Otis (Noah Jupe) on the set of his TV show (with scenes reminiscent of Even Stevens) and his life with his father, James (Shia LaBeouf). Their life, in a motel complex somewhere in LA, is not the life you’d expect a child star to live. Otis often walks himself home and steals food from the set. While his dad grows weed in secret by the freeway and attends AA meetings regularly. It is not the lifestyle that comes to mind when you think of the ‘Hollywood Elite’ who are so often pontificated about.

This life couldn’t be further from that of the Kardashian’s or any other Hollywood ‘royalty’ we have become used to. Otis’s dad refuses to hold his hand anywhere people might see them, he doesn’t want to be seen to be soft or caring. He is an addict, four years sober, who didn’t achieve what he wanted. He is a former clown and performer who, after an arrest and sexual assault allegation, found himself divorced and working for his prepubescent son. He is an abuser, emotionally and physically. He’s a man in pain. In some moments we feel his pain and at others, we detest him – sometimes feeling both simultaneously. We see his hurt, we see its roots and we see its reach.

Can we inherit pain? If those around us, who raise us, are racked with hurt do we then carry that burden too? How do we take that on? How does it manifest within us? How does it hinder us, grip us, affect us? Some scientists believe that the trauma of our parents changes our genetic markers while others disagree. Either way, growing up near so much pain is bound to have an effect and Honey Boy wants to understand that effect, to inspect it, and portray it.

Har’el’s direction does just that by cutting right through to the essence in this, her fiction film debut. Her ability to jump from bombastic montages set to thumping hip-hop to quiet, sombre, introspection is masterful. She straddles the narrative and the avant-garde with ease, superbly creating a dreamlike, hazy, feel to the overall film while continually rooting it in reality. She makes the film feel like memory and reality are converging on each other, the line between them becoming hazier with each scene but then, all at once, plummeting back into certainty. She continually charms you with humour and light before shocking you with aggression and gloom. It’s LeBeouf’s world but Har’el weaves it into a tapestry that is complex and disarming.

Har’el is also skilled with actors. LeBeouf’s performance is a career-best as he draws the character, based on his own father, in the grey areas. Outside of LaBeouf, there isn’t a dud performance to be seen. Relative newcomer Noah Jupe shines as a young boy managing his father’s temper and expectations while elsewhere Lucas Hedges continues to prove he’s one of cinema’s most interesting and versatile talents as the older Otis. FKA Twigs (in her film debut) exudes cosiness and melancholy as the girl growing up across the street from Otis, her performance is deeply rooted in physicality and quietness. Even Natasha Lyonne, though never seen on screen, provides audio cameo in one of the films funniest yet tragic scenes as Otis’s mother.

Honey Boy, at its core, is a portrait of broken people. From those who are trying to build themselves again and those who have shattered beyond repair. It’s about addiction and the ways in which we become our parents. We watch their demise, their mistakes, and then do the same thing in a way that feels almost inevitable, unavoidable, and mythic in its tragic nature. The film itself feels like therapy for its writer but not in a way that feels solipsistic or melodramatic. It feels deeply personal and intimate yet never closed off. It feels like Honey Boy is an example of something not often seen, in which an artist abandons their ego, owns up to their mistakes, and cuts through all the noise to tell an honest, human, story.

Rating:  (4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

Honey Boy is scheduled for release in December.

Also Read: The Lighthouse (Review)

![Online Film Festivals [Source Freepik and Wikipedia]](https://bigpicturefilmclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/online-film-festivals-Source-Freepik-and-Wikipedia-958x575.jpeg)