For this second instalment of our Global Cinema Spotlight series, we’re taking you to Brazil. Born in the 1960s and 70s in response to political upheaval, Cinema Novo transformed Brazilian cinema by presenting raw, socially conscious films with a unique aesthetic that is quintessentially Brazilian. ‘Cinema Novo’ simply means ‘New Cinema’ in Portuguese, the national language of Brazil. Let’s dive right into the history and evolution of this regional film industry.

A Brief History of Cinema Novo

Although the term ‘Cinema Novo’ has been used since the 60s, it is more of a retrospective term. The filmmakers of the time did not actively create films to fit into the description of Cinema Novo. It was an open practice which evolved naturally alongside the political and cultural changes of the time.

In the 1950s, Brazil mostly produced comedic musicals called chanchadas in the style of Old Hollywood. However, at the end of the decade, Brazilian films began to focus more on topics of social justice. This was as the country faced political upheaval as it entered the eras of Brazilian Presidents Juscelino Kubitschek and João Goulart. Cinema Novo did not have a defined style, but it picked inspiration from European film movements like French New Wave and Italian Neorealism.

The French New Wave saw the popularisation of the ‘auteur’ theory, which views the director as the creative lead of a film and therefore its author. Italian Neorealism was a style of politically-driven filmmaking in Italy following the 1943 Italian Spring. It explored topics like poverty and injustice, and Cinema Novo followed in this regard. The onset of Cinema Novo was also the first time Brazilian film began to receive international critical acclaim.

Cinema Novo is often divided into three phases:

Phase One (1960-1964)

The beginning of the movement focused on political themes like poverty, racism and social inequality. Violence was a common denominator which reflected the frustration of the society of the time. Films were often shot in black and white as a stylistic choice that deviated from the more polished Hollywood-esque style. The economic instability of Brazil was reflected in the lowered technical precision since filmmakers lacked the funds for higher-quality equipment. Glauber Rocha, who released the cinematic classic Black God, White Devil in 1964, was one of the notable directors of this phase.

Phase Two (1964-1968)

This phase was a reaction to the overthrow of the popular President João Goulart. The population faced disillusionment as many of his progressive changes were rolled back after the military coup. The pro-democracy ideals of the first phase began to seem unrealistic, and filmmakers began to move towards commercialization. The ‘aesthetic of hunger’ which was popular in the first phase gave way to a concentration on middle-class protagonists. This was a bid to create films more relatable to a larger audience. There was also a move from black and white to colour. This was first seen in Leon Hirzshman’s Garota de Ipanema (The Girl from Ipanema) (1967), one of the quintessential films of this time.

Phase Three (1968-1972)

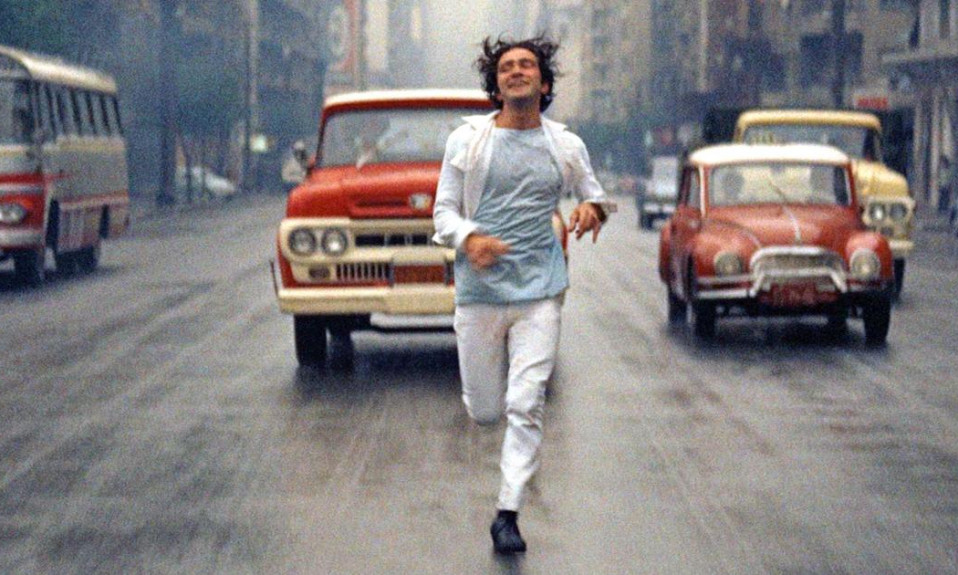

The last phase of the movement is sometimes referred to as the cannibal-tropicalist phase. Its tropical nature refers to the return to colourful aesthetics reflecting the Brazilian jungle. These had been popular before Cinema Novo. Cannibalism, in this case, was both literal and metaphorical. The best example of this is Rocha’s black comedy Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês (How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman) (1971). The film involved the literal cannibalism of a Frenchman, to represent how necessary violence is in enacting social change.

Impact

Cinema Novo had a definite end in the 70s with Brazilian film moving towards more commercial projects and government-backed film under the Embrafilme company. In spite of this, it has had a lasting impact. Cinema Novo is considered the beginning of the Third Cinema, a wave of socio-political cinema that popped up all across the globe. From Hong Kong to Australia and everywhere in between, the movement of socially conscious films changed how we view cinema. Eryk Rocha, the son of Glauber Rocha, paid homage to the movement through the documentary Cinema Nova (2014) at the Cannes Film Festival.

Also Read: Global Cinema Spotlight: Lollywood

Also Read: Interview: City of God’s Alexandre Rodrigues Discusses The Film’s Impact 20 Years Later