“He’s just eaten that dog, hasn’t he?”

My child’s reaction to her first viewing of Jurassic Park 2, when the T-Rex has a kennel hanging out of its mouth, and my first foray into dealing with violence in a film which I definitely should not have let my 3-year-old watch. That particular film was rated PG – parental guidance – but I was looking at it through the rose-tinted haze of nostalgia, not the more sensible reasoning that live-action, carnivorous dinosaurs might not be the best viewing for my pre-schooler.

This particular incident didn’t have any long-term damage, as far as I can tell, there were no nightmares and she still says her favourite dinosaur is a T-Rex. But what of the claims that violence in films and television is having a detrimental effect on young people who are ignoring the age rating and watching? Can on-screen violence lead to deviant behaviour in the real world?

In Britain, film classification is decided by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC). During this process, several factors are taken into account such as discrimination, imitable behaviour, language, drugs, nudity, sex, sexual violence, theme and violence. However, public opinion is also taken into consideration and, as this changes, so does the classification of certain films. This means that as certain topics become less of a taboo, then they are less likely to shock audiences and so require a less severe age rating. However, the group is aware that younger audiences are more likely to watch age-inappropriate movies at home when they are released on DVD or streaming services. They provide descriptions of the issues found in films in a bid to educate people before watching.

So what is meant by “violent imagery”? When classifying a film, the BBFC lists the following as issues which will be put a production into a higher categorisation:

- the portrayal of violence as a normal solution to problems

- heroes who inflict pain and injury

- callousness towards victims

- the encouragement of aggressive attitudes

- characters taking pleasure in pain or humiliation

- the glorification or glamorisation of violence

If films are seen to pose a risk to audiences they can be asked to cut certain parts out or, in some cases, be refused classification.

Although it is clear that extremely distressing scenes could pose a risk to audiences, particularly to those too young to fully grasp the context within which the violence is set, can individual acts of violence be directly attributed to movies?

In 1993, movie violence and its potential impact on young audiences were highlighted in the James Bulger murder trial. Initially, the Judge, Mr Justice Morland, claimed that exposure to violent videos might have encouraged the actions of the two 11-year-old killers. The film in question was Child’s Play 3. As a result of its link to the trial, the title was withdrawn from shelves and removed from television schedules at the time. Police refuted any link between the film and the actions of the two boys. But this isn’t the first and only time that connections have been made between violence on screen having a direct link with violent actions.

In a study conducted by Dr Nelly Alia-Klein of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and posted in the science journal PLOS ONE, it was found that watching violent images does make people more aggressive – but only if they are of a violent disposition, to begin with. The study focused on two groups of men – one group was inherently more aggressive with some having a history of physical assault, while the other group was much calmer. When shown the violent imagery, the group that was predisposed to aggression showed less activity in the area of the brain which controls emotional reactions to situations; basically, they were showing signs of less self-control. However, aggression is a trait that develops from childhood so if media does have an impact on people then this is something that is part of their nature from a young age rather than suddenly being impacted by what they see on screen.

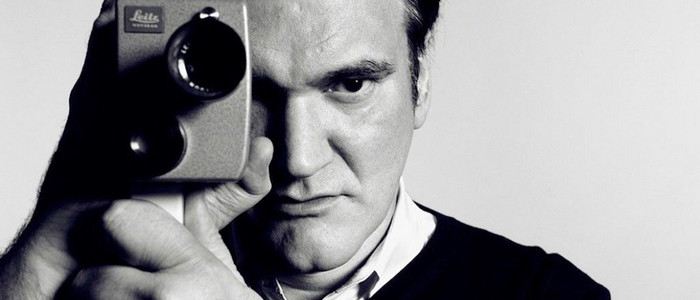

So what about the filmmakers themselves? Should they take more responsibility for what is shown to audiences or should they be allowed to produce whatever they want in the name of “creative license”? Quentin Tarantino has been described as one of the most violent filmmakers of this time and

he is unapologetic about this. Tarantino does not see himself as responsible for the actions of those who watch his movies and sees screen

violence and violence in reality as two separate entities. In films such as Django Unchained, Tarantino argues that he is showing

the brutality of reality at the time, something which he feels people need to be aware of. The same argument could be applied to 12 Years a Slave. Tarantino mentions that in his films the victim often becomes the victor. But it is argued that, where a character’s use of excessive violence is seen as a positive thing,

this can create negative role models for young people. Rambo, Terminator, the list goes on. The characters are predominantly male and this type of role model can only feed into toxic masculinity which makes boys and men feel that violence and aggression are the only acceptable ways of expressing themselves.

But is all violence the same? In a word, no. Let’s face it, animated characters fighting one another is never going to compare to that head popping scene in Game of Thrones (I can still hear it sometimes!) but the animated violence is still going to have some sort of impact on younger audiences. The important thing is to educate younger audiences about violence in films and their own emotional intelligence to deal with what they see. This is difficult in a world which is becoming more and more desensitised to images due to things being shared constantly via social media and children now having easier access to things they should not be viewing at a young age.

The most important thing we can do to educate audiences is to talk about the issues. Focusing on media literacy in schools is a massive step in helping make topics less frightening. Being aware of fake news is something that children need to learn and it’s surprising, as a teacher myself, how many false ideas students believe to be true because of what they have heard or read in the media. My daughter recently asked why a man had put a bomb on the tube in London. A question which caught me very much off guard but my job was to answer her in a way that wouldn’t frighten her.

We can shield our children as best we can but banning these things is not really the answer – this often gives a violent film cult status. We just need to answer their questions and educate ourselves. Or, as the Index on Censorship puts it;

“tackle actual violence, not ideas and opinions.” Maybe just keep the 18 films on the shelves that are out of reach too!

![Simpsons mob against unpopular opinions [Source GQ]](https://bigpicturefilmclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Simpsons-Mob-Source-GQ-958x575.jpg)