As 2020 drew to a close, writers and critics began to assess the year in terms of how film and television had managed (or struggled) as a result of the global pandemic. It was at this point that one writer’s assessment caught Twitter’s attention.

Julia Alexander’s article for The Verge proclaimed that a year without Marvel movies “left a pop culture void”. Admittedly, her central reference point was one that I, too, found somewhat moving; a packed movie theatre screaming in wild excitement during a screening of Avengers: Endgame in 2019. It wasn’t that I found that particular movie scene as rousingly exhilarating as those fans did on opening night, but I did sympathise with the desire to be seated in a full cinema again.

Where Alexander lost me – and quite a few others, it seems – was in her conclusion that 2020, the first year since 2009 which lacked the release of a Marvel movie, had created an“absence of a very specific kind of excitement”. While she admits that other films can generate discussion, memes and discourse, none can do so quite like a Marvel film can. In some ways this is true, but this phenomenon doesn’t just extend to Marvel movies; any type of superhero tent-pole designed as a marketing ad first and a film second will create this kind of buzz.

Over the Christmas period, Wonder Woman: 1984 found itself at the centre of this familiar blockbuster storm. Released simultaneously in theatres worldwide and on HBO Max in the US, it garnered both harsh criticism and intense defence. The group against the film (of which I, admittedly, am a member) thought it to be bland, nonsensical, and oddly racist. Those for the film thought its critics were paid off as part of some wider conspiracy against DC or floated theories that, due to most Americans watching it at home, they disliked WW84 because they were easily distracted by their phones.

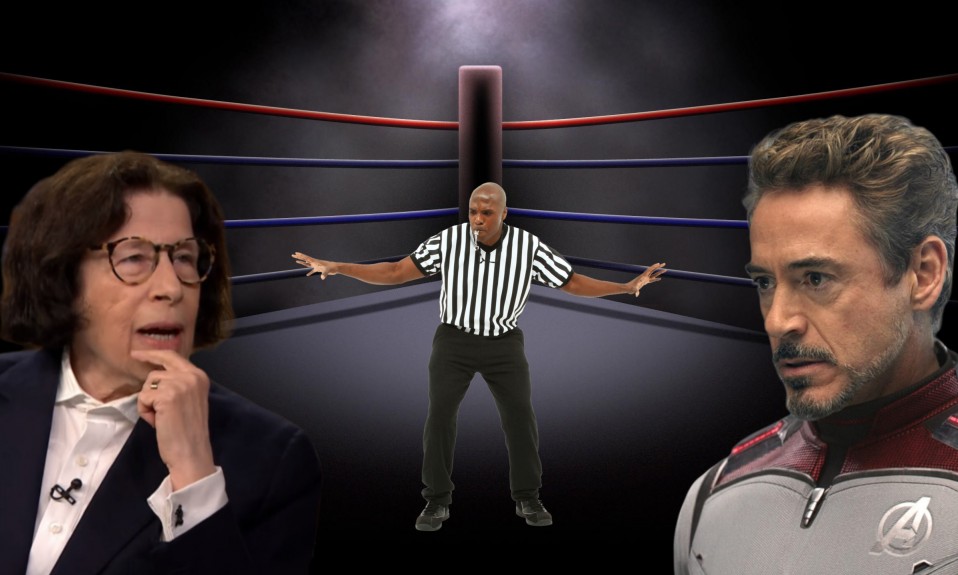

This is a familiar story: the internet whipping itself into a frenzy over the latest comic book movie. Last year, it was Joker. In previous years it’s been Man of Steel, Aquaman, X-Men, or some other such champion ‘man’. As Jia Tolentino wrote in Trick Mirror, the internet thrives on its ability to maximise our “sense of opposition”. As such, we are divided into two cultural camps: the childish-unintelligent-bro who adores these movies, and the snobby-elitist who considers the existence of such franchise films to be the very death of cinema itself.

This divide might seem overly simplistic and, in a way, it is, but its existence provides what the internet needs in order to thrive: clicks.

Think back to when Martin Scorsese decried superhero movies as not being cinema, or when Stephen Spielberg blasted Netflix. How many think pieces, hot takes and Tweets did that generate? A lot. One person’s opinion requires a near-immediate response, and that rebuttal requires one too until the original point is so cannibalised it is almost unrecognisable (hell, I’m even contributing to the phenomenon now with this column!).

This discourse seems to be shifting and distracting from the real issue: that audiences have simply become lax in what they will accept as good. This might be as a result of spending a decade arguing that the thing they enjoy is worth enjoying. It may also be that those aforementioned snobby-elites have forgotten that maybe there is some joy to be had or fun to be shared in the specific cultural experience of the superhero movie. Who’s to say?

Well, Fran Lebowitz is to say. In a recent clip that surfaced on Twitter from the documentary Public Speaking, Lebowitz discusses an audience’s role in maintaining the quality of the culture it consumes. She explains plainly that as a particular audience – one that paid attention and valued quality – died out due to the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, it gave way to a different, more accepting, one; a group that were happy to get what they were given and were content to simply like it. She also attributes the decline in culture to the fact that many great artists and filmmakers were also lost during this time.

I would say that, in 2020, we do a have a pop culture void – but it isn’t what Alexander reckons it to be. At the centre of our culture we have these five-hundred million dollar movies that, because they’re primarily considered a product, have to be bankable and provide profit. How do studios plan to recoup their investment? By presenting something that will appeal to as many people as possible while simultaneously saying nothing that might offend (in either direction) or indeed say anything at all beyond a basic, agreeable message like “girl power” or “good triumphs evil”.

Instead of focusing on this, putting our money where our mouth is and demanding better, we simply feed into the model of opposition and say: ‘it’s me, and not you, who is right about this’. We seem to just accept that DC plans to release six movies a year from here on out, or that Disney recently vomited up plans for over fifty-two new Star Wars, Marvel, and other franchise entries over the coming years.

So yes, there is a cultural void. One into which we just keep throwing money and time, until nothing matters at all.

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On 2020 in Film

More On This Topic: Stand Off: Superheroes Vs Art