A friend told me recently that she didn’t think of me as someone who fell. “I can’t picture it,” she said. “I’ve seen other people trip or end up flat on their face, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen you do it.” This was jarring to me. I felt I’d spent most of my teenage years stumbling around and had never been sure on my feet. This seemed especially so when I was drunk, lolling around on city streets, never upright. Yet, I wondered afterwards, as I got ready for bed that night, weaving through all the trip hazards scattered across my bedroom floor if it was more about how I appeared; the way I’d tried to position myself. To fall is to have no control. It is to be overwhelmed by a force you cannot fight against. That might be gravity alone, or gravity combined with a shove, an uneven paving stone, or an unstable foundation. It is to be, for the period you’re falling, unable to save yourself. I had spent a large portion of my twenties trying to create the image of a person who was managing, who stood squarely on two feet and could not be shaken. This was not true. I was very much a person who was falling.

In Disney’s Alice in Wonderland from 1951, a cartoon I watched a lot as a kid, Alice follows the rabbit into the hole in the ground and falls into pitch darkness. She quickly accepts her fate, calmly waving her cat goodbye before settling into the descent. Her dress catches the air and becomes a sort of parachute, reducing the velocity of her fall into something more like floating. “After this,” she says, looking down into the total blackness, “I shall think nothing of falling down the stairs.” When she manages to turn on a lamp, light fills the rabbit hole, and a series of mirrors, paintings, and tapestries move past her. She picks up a book from a floating table and flicks through its pages. She lands neatly on a rocking chair that’s falling too, but quickly slips off it. Despite the fall being substantial, Alice doesn’t seem scared. She’s unperturbed by what might be at the bottom. Instead, she questions where she might end up, an implicit faith that she is not falling to her death but into something else.

The word “fall” has many uses. We can fall into and out of things; we can fall over others. Things can fall apart, their very essence slipping away physically and metaphorically. We can fall in love, a phrase that conjures the stomach-churning fear of the drop just as much as any other. In America, Fall marks the coming of Winter. To fall is both a feeling and a practical danger. The first person narrator of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves speaks of a symbolic falling. “Alone, I often fall down into nothingness,” she says. “I must push my foot stealthily lest I should fall off the edge of the world into nothingness.”

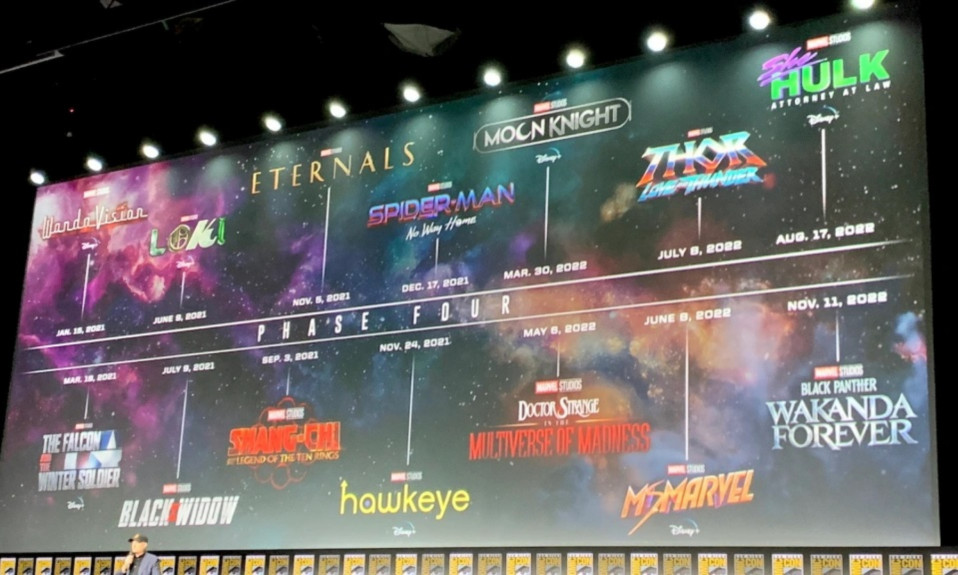

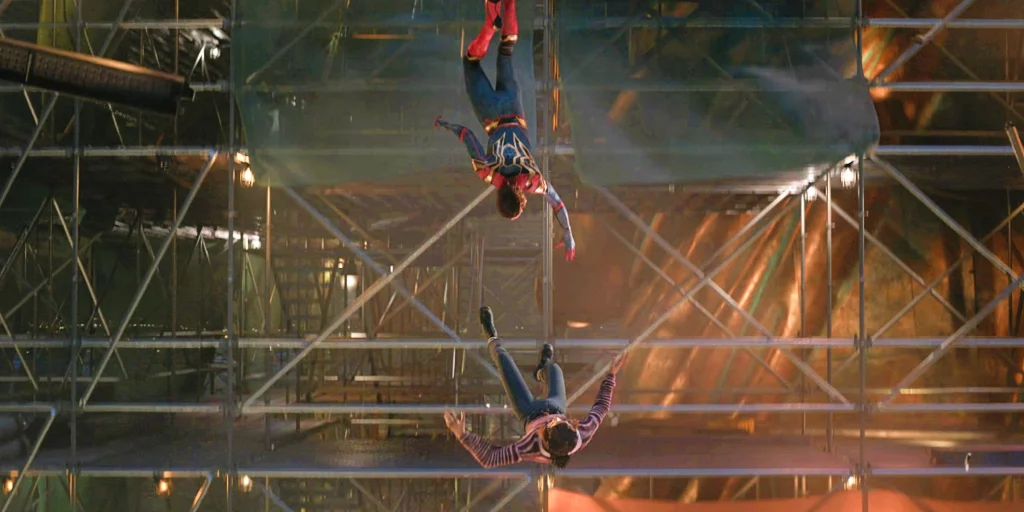

The terror of falling, then, comes not from the drop but from our ability to see how it will end, and where we will land. If we can see the bottom, and calculate the risks, then it is a jump; out a window, from a plane, onto a moving train. A jump gone wrong becomes a fall. To fall is to feel gravity unexpectedly or against your own will. Falling is not a choice. In comic book movies, most notably several Spider-Man films, the female characters fall so they can be caught. Spider-Man swings into action, grabbing the falling women by their waist and taking them to safety. They are dropped from great heights, and the threat comes from the idea that they will fall to their deaths.

Falling, however, is a guiltless way to die. The villains of Disney movies often fall to their deaths, so the hero cannot be blamed. They disappear down into dark trenches, off the edges of cliffs and into total darkness, their mangled bodies hidden from children’s watching eyes, and only when you’re an adult do you think of where they end up, of the gruesome splat that is suggested. The conservative values that have always haunted mainstream cinema mean that movies need morals. Bad guys need to be punished; often, this means they need to die, but a hero can’t kill. The villains fall to their deaths and do so by their own hand. They’re too greedy and make one final grab for power or revenge. The female villain in Indiana Jones and The Last Crusade dies by falling into a hole in the ground, one that has opened up because she has disobeyed the temple’s rules and taken the Holy Grail over the threshold. Yet she is desperate to keep the treasure, entranced by the power it holds. It has landed on a ledge just below her and, with manic eyes and a grin of total desire, she reaches out for it. The hero holds her by one hand and begs for the other, the one outstretched across the ravine. But she refuses and falls down into an unknown place, into the mists that lurk below.

When I started to think about falling earlier this week, I found a supercut someone made online of famous falls in movies. Cut together, the bodies moving through the air create something like a ballet. Their movements are matched and, each time, my stomach lurches as they tip over the edge. At first, there is the danger as people get too close to the edge, followed by a glimpse of the height. The two together suggest panic. Then there is the letting go, the slip, the trip, the push, which means someone is falling. In the supercut, the music kicks in. The fear in people’s eyes is emphasised, the plummet less of a spectacle than the feeling it induces. The arms flail as they desperately try to prevent the inevitable and then it’s over. They are caught or they are gone.

Over the past few months, I have felt like I am falling. Toward what? I don’t know. The question continually seems to be whether I will land and where that will be. My falling is best encapsulated in the Bruegel painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus from the 1500s. The painting shows a beautiful vista, a calm turquoise sea and the yellow sun setting in the background. This is the scene through which Icarus has plummeted to his death, but no one saw it happen. The people in the foreground go on with their tasks, herding sheep and ploughing fields. The ships remain stoic in the distance but, in the bottom right-hand corner, a body splashes around. Its legs jut out from the ocean, its head submerged. Is this Icarus? His wings melted by the sun, and so he has fallen into the ocean? He is drowning in the corner of the painting, and nobody is looking. No one has seen him go. What does it mean to fall when it isn’t up on the screen? How does a person fall in public and no one sees it? What happens when it’s all over?

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On Feeling Stuck