The talented Guinevere Turner is an acclaimed screenwriter and director who penned films as ‘American Psycho’ (2000), ‘The Notorious Bettie Page’ (2005), and ‘Charlie Says’ (2019), Turner also wrote and played a recurring role on Showtime’s groundbreaking series ‘The L Word’ (2004 – 2009). Decades ago, she came into the scene through lesbian rom-coms ‘Go Fish’ (1994) and ‘The Watermelon Woman’ (1996). Turner is also a Cinema professor at Syracuse University and has taught at New York University, Columbia University, UCLA among others and all of this while having the appeal of a Golden Age Hollywood star.

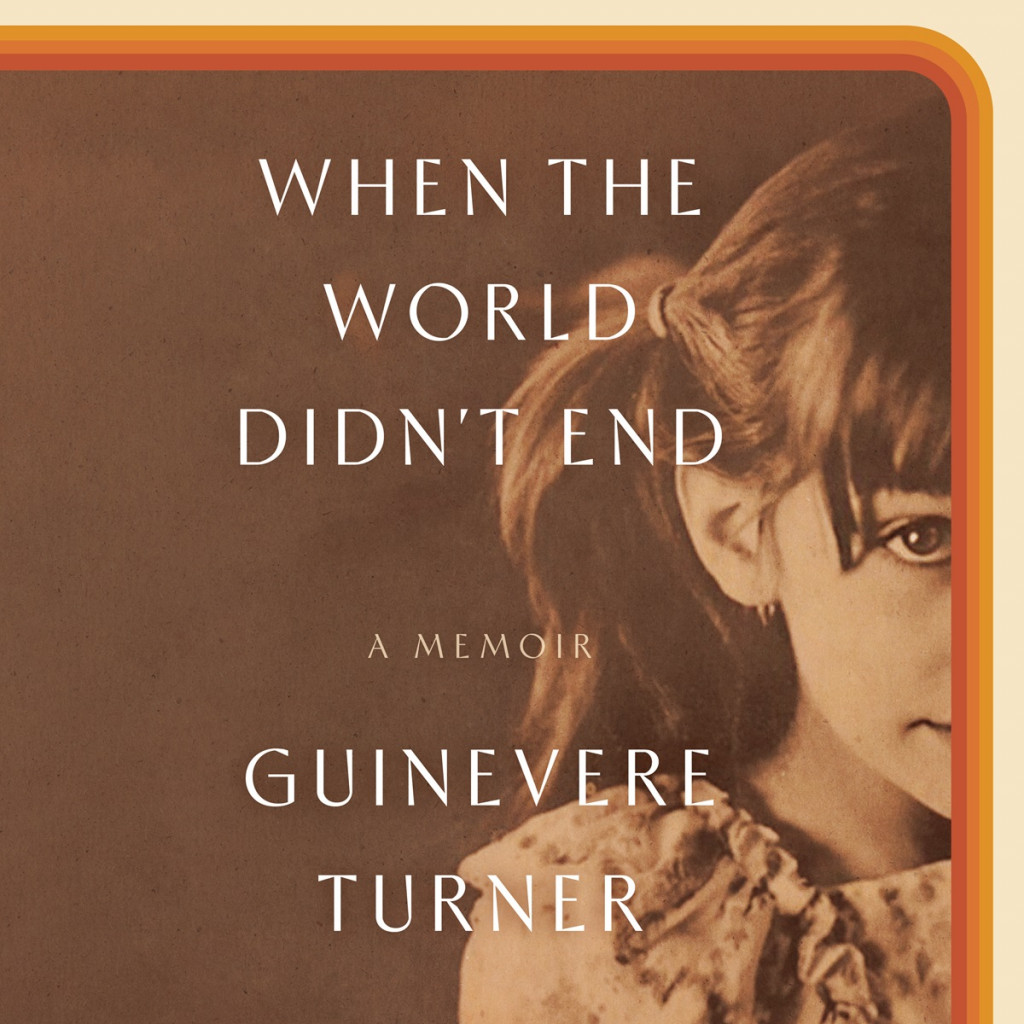

Still, although known for her maverick writing style, in 2019 Turner wrote an essay for The New Yorker that told her ordeal about growing up as a member of the Lyman Family cult and by tail end of last season she published the memoir When the World Didn’t End (Crown Publishing, Penguin Random Books, 2023).

Turner is known for the creative partnership with veteran director Mary Harron which generated four movies, among them the horror satire ‘American Psycho’ which follows yuppie serial killer Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale). As an independent artist Turner broke through with Cheryl Dunye’s ‘The Watermelon Woman’ and Rose Troche’s ‘Go Fish,’ with the latter she would work together in ‘The L Word.’

Meanwhile When the World Didn’t End allows us to understand the places she comes from as she was raised in a secluded cult managed by Melvin “Mel” Lyman, a self-proclaimed saviour who defended their isolation from a world that “had lost its way.”

In a video interview with The Big Picture Film Club, Guinevere Turner, one of the brightest of her generation, speaks about the creative process, the Harron partnership, pioneering lesbian representativity in film and TV, ‘American Psycho’s cultural impact and coping with trauma while working on her memoir.

Gabriel Leão: You’ve been contacted by publishing houses to write about your early life experiences with the Lyman Family Cult for decades. What made you feel like writing it at this stage of your life?

Guinevere Turner: The reason I wrote the book is because I wrote the movie ‘Charlie Says’ which is about the women who killed for Charles Manson, and their time in prison.

It was then that I realized that I’ve been avoiding talking about my childhood in the press. Because often I had been asked; however, it wasn’t relevant to the movie I was promoting, and I know how it is relevant to talk about it now.

In 2019, I wrote a piece that was published at the New Yorker Magazine, and it was one of their top 25 most read stories of the year and people from all sorts of platforms reached out to me, regular people who had been in cults or raised in cults like me, and then also publishers and agents saying: “Are you going to write a book about this?”

For years people had been saying: “You should write a movie or a TV show about it.” Because that is what I do, and I thought: “I got to write a book first to control how I’m going to tell this story.” It is tough to work through all that with a crew, a cast, and opinions of people with money.

Therefore, it seemed like now was the time to write the book, I wasn’t ready before, but then the opportunity was here. Hence, I decided to tackle it and it was not easy.

I haven’t written a book before, I write screenplays. The publishing house said: “Here is your contract, and you have two years.” I thought: “I’m not going to need two years.” And two years later I was astonished and figured out that I need two years, so I had to use these two years better.

GL: One of your most known working partnerships in cinema is with film director Mary Harron. How do you both operate, and why does it work so well?

GT: It is funny, I was just talking with her on the phone, because we are in different places, we are just about to make our fourth film together that we wrote, and she is directing. It has been a while since we’ve written together and just because we’ve been doing other things, and I forgot how much we laughed, we exceptionally have a dark humour which really makes us laugh.

We try to be in the same place, but for years I’ve been living in LA, and she lives in New York, and now I’m in Syracuse, New York which is just five hours North from New York City. We’ve known each other so well at this point, it is our fourth film and we’ve written other scripts together. We like to be in the same room because it is the reason that it works, and it was almost immediately as we met in 1997 and started to write together.

We are not competitive, and there is no sort of ego, so I’ll say some really dumb ideas and she will say really dumb ideas too. We are not embarrassed about that; we are not also shy to say: “I don’t think that is a good idea but what about this.”

There is a lot of ego in collaboration and sometimes people want their ideas to be the one that gets used, and with us is just the opposite, it flows easier in that way, and I think that is important as we are not competitive or self-conscious, we just try to make the best thing.

We have the same sense of humour, and although not all of our movies are funny, we have a sensibility in common, we work really well together. What is crazy is that when I met her, she was single, no kids, and we were just starting on our first project, and now her daughters are on their 20s and giving me notes and they give really good notes. I remember when I was in the hospital room, and they were born.

GL: One of the reasons you wrote When the World Didn’t End was working with the script of ‘Charlie Says.’ Do you see any similarities between the Manson Family and the Lyman Family?

GT: (Breaths)… There are many similarities. But that said as a person who studies about, has been in a community of cult survivors, deprogrammers, counsellors, and is very up on cults. The similarities across countries and decades of cults are kind of shocking sometimes. It is all just patriarchy on steroids and in the rare case when there is a woman in charge it is still power dynamics on steroids in which women and children usually suffer. I have never met Mel Lyman. I know Manson better than I know Lyman because I did a lot of research on Manson and he spoke every time a camera was pointed at him, not so for Lyman, and Manson lived about 30 years longer.

I don’t think Lyman cared about being famous, he cared about getting his music out there, about whatever his philosophy was, bringing people to a different kind of consciousness and way of being, whereas Charles Manson really wanted to be famous.

In my research, and in the way that I crafted my film, I really started to understand the reason that Manson practically lost his mind and started encouraging his followers to prepare for “The War,” “The Apocalypse,” and eventually killing these people. What else made the Manson Family infamous is because he realized he wasn’t going to get famous; therefore, he needed to crank up the stakes to keep his followers.

Manson was like this because he wasn’t going to get a record deal, on which he crafted the whole family around like he was going to get this deal, his music was going to get out to the world, and that didn’t happen. Manson was a con man; Lyman was an acid-using deep-thinking musician who got a lot of people to follow him though, still not always to everyone’s benefit. There is a lot of that man that I don’t know.

GL: Is there any possibility of When the World Didn’t End becoming a picture?

GT: Yes, I hope that it begins this year, I have just finished the script. Absolutely (want it), it was hard to write the book, to go through all of the press and talk about it, but also in both cases great. Still, it is very personal, has lots of traumas, and people connect to it in a way as they share their trauma. So, it is a lot and now I’m going to put myself through all of that again: write the script, get the movie made, go to the screenings, talk to the movie people, and journalists. I’m really putting myself through this several times, but I feel wise and strong enough to handle it without it really getting to me in the way it would when I was younger.

Because it has to do with my writing and I’m working on an adaptation to turn it into a screenplay and a movie or perhaps a limited series. It is too much story to fit into in just a 100-minute movie, but my manager was blunt: “We want it to be a movie.”

I tried, though I just wrote her last week and said: “I’m at the page length that an average feature film would be but I’m only twelve (years-old).” (Laughs)… Which is about the middle of the book. And she was like: “Maybe it is a limited series.”

It is hard because it is a difficult book to adapt and adapting difficult books is what I do, but not the ones that I’ve written.

It has hit me: “Who wrote this? How are we supposed to make this a visual thing?” Because so much of my book happens in my head, so much of it is what I’m thinking and not being able to really tell anyone while in screenwriting terms you give the character a best friend, a guru that they can talk to, you have voice over, but none of those things are true or seem right for this. I’m really challenged about how to make it cinematic, how to separate myself from the actual story, and just look at it as a professional. I feel very challenged, and it might be the most challenging experience I ever had.

GL: Another work featuring a toxic male figure is ‘American Psycho,’ which features Patrick Bateman, who is adored by bros and is the face of the sigma male movement. What are your feelings about Bateman’s position in culture?

GT: It is strange, surprising, and hilarious when it is not so disturbing, which is to say that there is passionate fanbase for this movie as we are still talking about this movie 24 years later which is great. I hope that everything that I make gets talked about 24 years later.

A part of the huge passionate fanbase of this movie are just toxic men who just didn’t get a whole layer of the movie, that it is a satire on a set of men, on commodification and capitalism at its worst. They think he is a “cool dude.” (Laughs).

That to me is the sort of thing you couldn’t do on purpose. I just assume that those that watch this movie understand that Patrick Bateman although handsome, flawlessly worked out, donning very expensive clothes, is still a desperate man who is killing to get noticed and still can’t be noticed.

A loser with all the worse kinds of hyperbolic male traits: he wants all the things, and it is not enough; women are just like nice suits to him, maybe not even that important; he is an actual murderer of women for sport, and everyone (in the movie) is like: “What?” (We both laugh).

I find him very interesting because this movie was not very well-loved when it came out in 2000, wasn’t well-reviewed, and at the premiere screening at the Sundance Festival it received awkward applauses at the end. It was painful.

But it has just gained momentum. Once, I asked my students who weren’t even born when it was released: “Why do you care?” One of the girls goes: “Memes. There is just so many memes, you have to know what it is.” (We both burst into laughter).

We made a very ‘memeable’ movie before memes were a thing.

GL: You’ve been for long a champion of LGBTQIA+ representativity on the screen, in particular lesbians. How do you feel about newer generations catching up with your early works, such as ‘Go Fish’ and ‘The Watermelon Woman’?

GT: Amazed and very pleased, especially in the case of ‘Go Fish.’ It is so very analogue (laughs)… We used (tele)phones and everything about it just feels very much of its time which was early 1990s. They just showed it as an anniversary screening at the Sundance Film Festival a few weeks ago and a young Brazilian woman was crying and told me: “I come from a different culture and things are different for LGBTQIA+ people in my country, but this movie has moved me so much, I feel like it is about me.”

That makes me happy because you really don’t know that if you made something universal until a lot of time goes by, and in the case of this movie 30 years.

I feel continuously surprised and sat through with it at Sundance, we laughed at ourselves, and we were so young, I was 24 (years-old) in that movie. It is also so interesting to have a record of yourself at such an age, not only what I looked like, but I wrote it, thus what I thought, my perspective on the world.

‘The Watermelon Woman,’ is so interesting because (sadly) people didn’t pay attention to it for like 25 years. Now, every time I turn around there is a still from it in something either about queer cinema, Black women directors, or what they call the construction of auto-fiction with Cheryl (Dunye) playing a Cheryl who is kind of her with this sort of half documentary style.

I was in my first semester here at Syracuse University, my students didn’t know, they hadn’t seen my name, they had just to take my class, and so it came up that I was talking, and I mentioned ‘American Psycho,’ then one of the kids checks his mobile and comebacks: “Excuse me, you wrote ‘American Psycho’?” And I was like: “Yeah, don’t you guys google your professors?”; “We didn’t know who you were. We didn’t have your name.”

And them everybody is googling it, and another student goes even more excited: “You were in ‘The Watermelon Woman’.” And I was like: “How these 19 years-old people knows this movie?!”

Apparently, it was a required class for freshman in this college, 90s queer cinema, and they show ‘The Watermelon Woman.’

GL: You also played an essential part in the writing of ‘The L Word,’ which you also named, and later, the series would have a sequel for a whole new generation. How do you feel about being part of and living through those days?

GT: It was my first and only time working in and writing for television. It is different from movies, it’s a room full of people, deadlines are strict, and it is fun; writing for film is so solitary, it is just Mary and me.

Before it had come out there is an excitement: “Is this going to work?”

It is the first television show that is specifically about lesbians ever, at least in North America. So, there is an energy about it: “How can we make this a fun show while also maintaining its politics?”, “How can we make it speak to lesbians, obviously our audience, but also to people outside of the community?” In the end, it has to be a good show, regardless of who it is about.

It was exciting, to write something in May and it is on TV on December. In film, something in May is like three years later (laughs) in May.

The TV show ‘Broad City,’ is about two millennials who are best friends, in one episode they mention both ‘American Psycho’ and ‘The L Word,’ and I was like: “I’m so famous.” (Laughs).

I worked with Rose (Troche) in ‘The L Word’ and ‘Go Fish,’ and it is interesting because a generation of lesbians grew up with the series; if we were told in our early 20s that there was going to be six seasons of a TV show that then would be turned into another TV show, and there would be a reality TV show that was just focused on lesbians, we probably would burst into tears of joy and say: “So many changes.” But I mean not that many changes.

What really happened was that networks and corporations realized that LGBTQIA+ people have buying power, and if you build it, we will watch it, especially lesbians as we were also starved for representation. They probably thought “fools” (of themselves) because they didn’t do it sooner. The show was well-received, it was on the cover of New York Magazine before it even came out. It is thrilling that the concept of ‘The L Word’ has become a shorthand for “lesbians,” a cultural mark, and a way of talking about a community, including making jokes that are not homophobic.

GL: How do you process having fans ranging from your queer stories and ‘American Psycho’?

GT: Hilarious. There is this small group of people who just love independent film who have seen both, but I think most of the fans of ‘Go Fish’ have never seen ‘American Psycho’ because, I, myself, would have never see ‘American Psycho,’ I probably would have eventually, but I would have been scared and I don’t like scary movies. And the idea of making those bros sit and go through ‘Go Fish’ and make those lesbians of my generation sit through ‘American Psycho’ (We both laugh), I’d love it. You know, we have many sides (gestures over her head), at least two, the one who can write satires about serial killers and the other who can write romantic comedies about lesbians.

Note: This interview has been condensed and edited for reading purposes.

Also Read: Iconic Scenes: American Psycho – Business Card Scene