Last week, as the 78th Venice Film Festival came to a close, Penelope Cruz received the Best Actress Award for her performance in Pedro Almodóvar’s latest melodrama, Parallel Mothers. In the film, Cruz plays Janis, a 40-year-old single mother raising a daughter in Madrid who receives some life-changing news, and critics have praised her performance as “sure-footed”, “astonishing”, and “formidable”. This latest film is the seventh Almodóvar and Cruz have made together. Previous outings have given us the loyal and criminal mother of Volver, the young nun of All About My Mother, and, most recently, Cruz’s tender performance as Jacinta in Almodóvar’s magnum opus Pain and Glory.

Since 1997, the pair have been an unstoppable force in Spanish cinema, a power second only to the genuine love they seem to share for each other. At the 72nd Oscars, when Almodóvar won Best Foreign Language Feature for All About My Mother, Cruz, alongside fellow Almodóvar staple Antonio Banderas, had the honour of giving it to him, shouting his name out like an excited school child as she opened the envelope. “He’s my safety net,” she told the press at Venice two weeks ago. “He can ask me to do something that can really scare me, but I know he will be there.”

I have long believed that the partnership between Almodóvar and Cruz is one of the greatest in cinema history, likely for the very reasons Cruz mentioned. Cruz’s performances for Almodóvar are fearless; they are risky and brutal, vulnerable and tender. That working relationship that blends with the personal offers us, the audience, hours of cinematic genius. Yet when the idea of actors and directors working in pairs comes up, the two are rarely mentioned. Instead, we hear tell of DiCaprio and Scorsese, or De Niro and Scorsese. People talk of Hitchcock and Stewart, Burton and Depp, Spielberg and Hanks. As if the only way greatness can be achieved is if it’s reached by two men – usually straight and white.

Those beacons of greatness, who often make heavily masculine and male-centric films, are why Cruz and Almodóvar are so often left out. “Great movies” are about violence, they are about men seeking revenge, they are about men on a mission, they are about men. Almodóvar’s movies, while occasionally violent, are often colourful melodramas, queer and camp, that exist on a different astral plane. They explore the lives of outsiders, of the working classes, of women and the world of sexuality. Yet when it comes to “greatness”, their films exist as victims of, as Emily Nussbaum once noted, “an unexamined hierarchy: the assumption that anything stylized (or formulaic, or pleasurable, or funny, or feminine, or explicit about sex rather than about violence, or made collaboratively) must be inferior.”

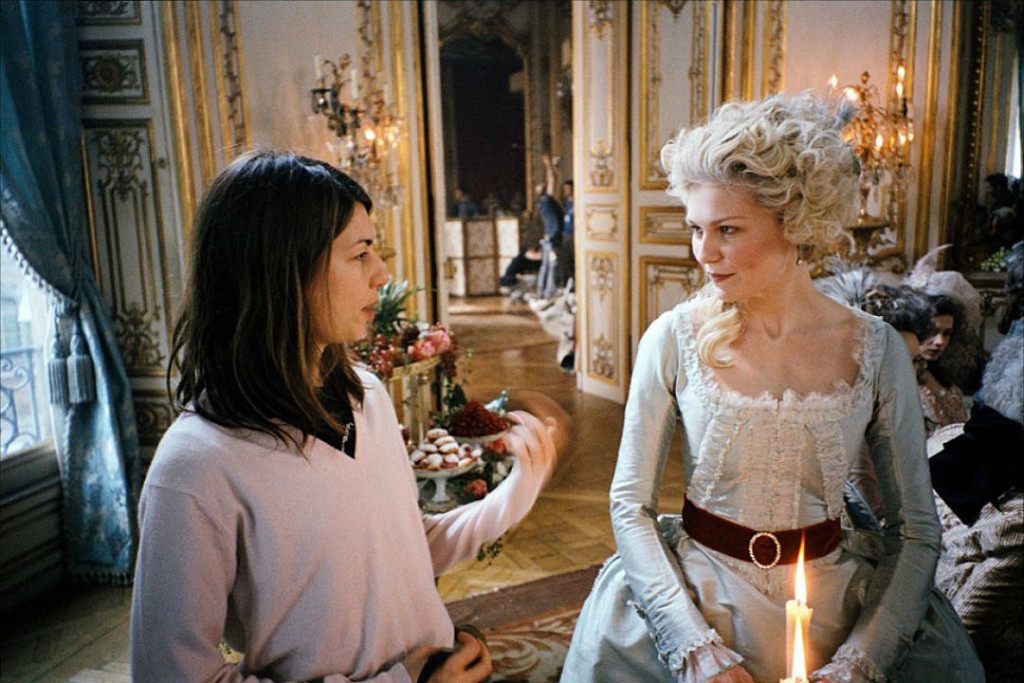

Almodóvar and Cruz are not alone in this rarely recognised space either. Catherine Keener has appeared in five of Nicole Holofcener’s six feature films, exploring the complexity of the female experience from their twenties into their forties. Sofia Coppola and Kirsten Dunst have done something similar, with Dunst appearing in four of Coppola’s films, each offering a nuanced look at the life of young women. Julianne Moore has appeared in three of Todd Haynes’ films, including a tremendous turn in the Douglas Sirk homage Far From Heaven. Michelle Williams has repeatedly blown audiences way in her films with Kelly Reichhardt, the next of which is currently in post-production. At the same time, Tilda Swinton exuded her now-trademark complexity in six of Derek Jarman’s films in the eighties and nineties before his death from an AIDS-related illness in 1994.

If this list seems overwhelmingly white, it’s because it is. While black men have found some repeated success in pairings like Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan, or Spike Lee with Samuel L. Jackson and Denzel Washington, they rarely get included in that pantheon of greatness. Though, admittedly, if their films conform to that idea of violence and masculinity as central, they tend to do better. As for women of colour, Ava DuVernay has worked with David Oyelowo three times, while Teyonah Parris appeared in Nia DaCosta’s recent Candyman reboot and is due to appear in The Marvels—the upcoming sequel to 2018’s Captain Marvel—directed by DaCosta.

The point of all this listing? For nearly a century, the film industry has continually pushed an unquestioned narrative onto its audience that male art is great art. Everything else is left out of those discussions. That which deals with the male experience is what cinema is all about, and whatever else filmmakers cover it does not hold that same value. Take, for example, the outcry each time it’s rightfully suggested that a number of women directors have been snubbed for Best Director any given year. “MaYBE iT’s AbOuT wHo iS bEtTer aT tHe jOb?” people scream on Twitter, battening down on the unquestioned assumption that all the men who are nominated are, ipso facto, better than the women who aren’t.

In her response to Lady Bird leaving the 2018 Oscars empty-handed, Hunter Harris wrote for Vulture that “Greta Gerwig made a movie about what generations of male auteurs saw only as background noise.” Specifically, she made a film about mothers and daughters. The characters who, in the movies of men, are often side-lined. They wait for their husbands to come home, they chastise them for making bad decisions, they complain, they put their feet up on the car dashboard for the camera to zoom in on, or, like Anna Paquin in Scorsese’s The Irishman, they have a single line (that amounts to seven words) in a movie that is basically the length of a mini-series.

This is not to say that straight male directors are incapable of understanding experiences outside their own; some do often, and do it well. Most, however, rarely do. Spielberg has overwhelmingly cast men as his leads. Scorsese’s movies often feature one woman at most amongst a sea of male violence, while Tarantino, for all his “feminist” hype, creates two-dimensional women that are reduced down to their bodies. It suggests, perhaps, a lack of empathy or interest in experiences outside their own which itself is cultivated by the very narrative their work upholds.

The straight male directors of today are not leading the charge in their male-led ideals but instead continuing a legacy that dates back decades. In Recollections of My Non-Existence, Rebecca Solnit writes that the constant centring of the straight white male experience is a longstanding problem, with broader effects than we may think. There is a problem “with those who spend too little time being anyone else; it stunts the imagination in which empathy takes root, that empathy that is a capacity to shape-shift and roam out of sole self.” For women, people of colour, disabled folk, and queers, we spent our childhoods being someone else. We had to. Imagination was the centrepiece of our childhood, finding ways wherever we could. It is where we learned to empathise

Perhaps, as a queer person whose strongest friendships have often been with women, I see something of myself in the work of Almodóvar and Cruz, knowing how specific and open that bond can be. Perhaps, whilst also being a social-political vendetta I’m writing about, it is also a personal one. I find it frustrating each time I read a list of “Best Actor and Director Pairings” and they’re not on it. I find it disheartening that work that questions the idea of the patriarchy is subjugated to the work that upholds it.

Also Read: How Film Changed Me: On The Hollywood Trickle-Down